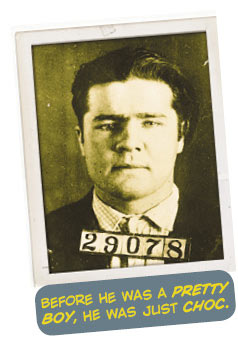

Before he was known across the country as Pretty Boy Floyd, the outlaw Charles Floyd was known in his Eastern Oklahoma hometown as “Choc.”

This came from the fact that the young Floyd had a powerful taste for Choctaw beer, called “choc” for short. In Clint Eastwood’s classic western movie The Outlaw Josey Wales, a nervous trading post proprietor tells Wales, “I’ve got some beer. Some good-brewed choc. It’s on the house.” The term “Choctaw beer” or “choc” appears frequently in the Western and outlaw literature of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, but few today remember what it was.

This came from the fact that the young Floyd had a powerful taste for Choctaw beer, called “choc” for short. In Clint Eastwood’s classic western movie The Outlaw Josey Wales, a nervous trading post proprietor tells Wales, “I’ve got some beer. Some good-brewed choc. It’s on the house.” The term “Choctaw beer” or “choc” appears frequently in the Western and outlaw literature of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, but few today remember what it was.

Choctaw beer is not a brand, but rather a term for a distinct tradition of illegal, self-manufactured beer, just as moonshine or white lightning are terms for a distinct tradition of illegal, self-manufactured corn liquor. Aside from white lightning, Choctaw beer was the most iconic—and roughest—alcoholic beverage of the old West. As an Oklahoma newspaper remarked in 1906: “A few swigs of the stuff will make an ordinary cottontail rabbit spit in the face of a bulldog.”

The beer is named for its creators, the Choctaw Indians of Oklahoma. The Choctaw are indigenous to the Southeastern United States, but the majority of them were forcibly removed to Indian Territory (in current-day Oklahoma) by the federal government following the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The act violated previous treaties with the Choctaws and other tribes and culminated in the infamous Trail of Tears. Nearly 2,500 Choctaws died during this brutal deportation from their homeland. Eventually the Choctaws settled in their new homeland, which now encompassed the southeastern corner of Indian Territory.

There was a kick to choc that high alcohol content alone couldn’t explain, and the frequent addition of snuff and other forms of tobacco was probably a big part of it.

When the railroads began stretching westward across the U.S. in the 1870s, railroad workers poured into the Choctaw Nation, soon followed by coal miners. In the 1955 edition of the Chronicles of Oklahoma, Stanley Clark writes, “These men were of American, English, Irish, Scotch and Welsh descent mainly from the coal fields of Pennsylvania. The first Italians recruited for the mines arrived at McAlester in 1874; by 1883 it was estimated 300 families were in the Krebs-McAlester area. Lithuanians in 1875 and Slovaks in 1883 were brought from the coal fields of Illinois and Pennsylvania.”Among other regulations, federal law prohibited the importation of alcohol into Indian Territory, and internal tribal laws reinforced this policy. It isn’t exactly clear when Choctaw families began manufacturing their namesake beer, but the homebrew tradition was firmly established on the farms of the Choctaw Nation by the mid-19th century.

It’s rough work, gouging coal from the bowels of the earth, so when they finished their long shifts the miners naturally wanted a drink. Unfortunately, the mines were located in Indian Territory. There were none of the saloons that dotted the rest of the West, and unlike with the coal fields of West Virginia and Kentucky, there were no whiskey stills hidden in adjacent hills. So the miners purchased Choctaw beer from the locals. A 1909 edition of The American Brewers’ Review states, “In the mining region many of the miners are Hungarians, Poles, Irish, Italians, and Mexicans. They like Choctaw beer and often drink it to excess.”

In 1889, the Oklahoma Territory was opened to white settlement. The ensuing land rush overwhelmed the Choctaw Nation. The besieged tribe suffered thefts, violent crimes and murders at the hands of whites and other tribal members.

Among other results, this invasion increased the demand for Choctaw beer. Steven L. Sewell, who explored the history of Choctaw beer in an article for the Journal of Cultural Geography, writes, “Because most men spent much of their time down in the mines, women dominated the Choctaw beer industry.” While there were eventually brands of bottled, locally-distributed Choctaw beer, much of the trade was individual women making and selling their own concoctions. During these hard times, the choc trade was an economic necessity for many families.

The federal authorities were never happy with the widespread Choctaw beer trade. During the 1890s a series of contradictory rulings confused the issue of whether the territorial alcohol ban applied to beer or only hard liquor, whether the ban applied to U.S. citizens or only to tribal citizens, and whether the ban covered the manufacture of alcohol in Indian Territory or only the importation of alcohol into Indian Territory. Congress eventually clarified the issue with anti-beer legislation, but the temporary gray areas had helped choc brewers to flourish and gain a solid foothold. Local authorities were easily bribed, and when they weren’t, the risk of 30 days in jail wasn’t a serious deterrent to a profitable choc operation. There were also semi-legal workarounds—many sold Choctaw beer under the guise of a medicinal tonic, and local doctors attested to the health benefits of choc, arguing that it was healthier than the local water.

When Oklahoma joined the United States in 1907 it was as a “dry state,” a designation which had little effect on the underground choc trade. When drinkers in other states began to deal with the predations of Prohibition a dozen years later, Oklahoma’s drinkers were already decades deep into their love affair with illegal Choctaw beer.

“Choctaw beer was an important part of the culture of the Choctaw Nation,” writes Sewell. “While ‘choc’ originated with the Choctaws, it quickly became the favorite drink of every nationality and ethnic group in the Choctaw Nation.” Shortly after their arrival, Poles, Italians, and members of other immigrant groups had begun to not only guzzle choc, but manufacture and sell it as well. Residents of the Choctaw Nation area and the entire state of Oklahoma became fiercely loyal to the beverage. The Oklahoma Historical Society records an anonymous state resident of the mid-20th century as saying, “It won’t hurt nobody cause fruit’s good for ya, but it’ll make you drunker than a fool. Don’t put snuff in it, that would kill a dog! As good as it is, everybody should have two or three glasses a day. My family always felt good.”

There was a kick to choc that high alcohol content alone couldn’t explain, and the frequent addition of snuff and other forms of tobacco was probably a big part of it. The American Brewer’s Review asserted that “cocaine and other injurious drugs” were often added, but it’s unlikely that rural home brewers were spiking their choc with coke. However, fishberries (also known as Indian berries, or anamirta cocculus) were a common choc ingredient. Fishberries contain a powerful poison, and their primary use is stunning fish so they can be easily scooped up in a net.

Tobacco, “injurious drugs,” and fishberries aside, the basic ingredients of choc were what you’d expect from homebrewed beer: hops, barley malt, sugar, and yeast. Depending on the brewer—and what happened to be on hand—other grains or fruits such as oats, rice, corn, apples, peaches, and raisins could and would be thrown in as well.

In 1933 Congress passed the 21st Amendment, repealing Prohibition. Rather than returning completely to its own strict prohibition policies, the state of Oklahoma decided to allow the sale of 3.2 beer. While it is practically impossible to get drunk off of 3.2 beer, this decision signaled the slow decline of Choctaw beer in Oklahoma. People in search of more of a kick continued to manufacture and purchase choc for the next half-century, but once legal options emerged, the alternative beer economy gradually passed away. It eventually became cheaper and easier to just buy a case of Budweiser than to manufacture or buy choc.

The current wave of micro and homebrewing that is sweeping the nation, however, offers an excellent opportunity for a choc revival. If you are brewing beer at home (or work) do me a favor: forget about how smooth or balanced your beer should be, and recall a time when Americans packed their homebrew with tobacco and poison berries. Must everything taste like sunshine and flowers? Shouldn’t there be room for something that makes “an ordinary cottontail rabbit spit in the face of a bulldog”?

Let’s do this thing.