Hollywood has always sent mixed messages when it comes to booze.

At times it wholeheartedly celebrates drinking (The Thin Man, Animal House, Barfly), other times it will aggressively vilify it as a social evil. Some of these vilifications turn out to be fine movies, generally because they refrain from getting too maudlin and heavy-handed, and perhaps even make an attempt to present both sides of the story (The Lost Weekend, Days of Wine and Roses, and Leaving Las Vegas being prime examples).

Then there are those hysterical (in both senses of the word) films that are so eager to bash booze that they forget about things like plot and character development. These are the films we’ll be dissecting in a ten-part series featuring the worst drinking movies ever unleashed on the public. Let us begin at the bottom.

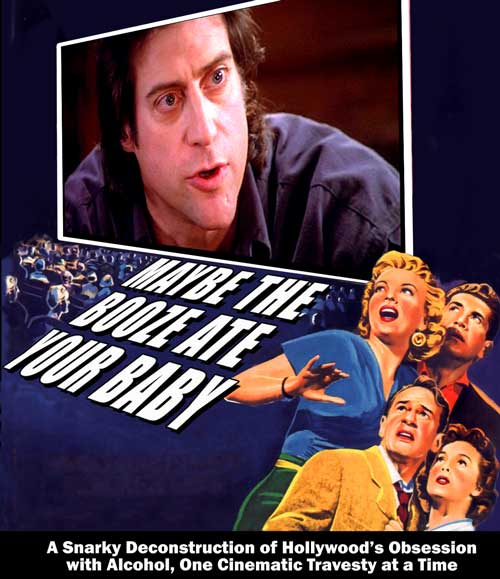

Drunks (1995)

It doesn’t take long to get the feeling that the screenplay for Drunks was penned by an eager college kid who’d snuck into Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and was naive enough to believe the, uh, exaggerations told by the attendees. I say exaggerations because we humans are an extremely competitive species and those striving to divorce themselves from alcohol are no different. If you’ve ever been to an AA meeting (and I have, purely for journalistic purposes, natch), you’ll immediately notice there is a strong element of one-upmanship: “You drank a fifth and beat your wife? Well, I drank two fifths and beat my wife, the neighbor’s wife, and some wife I just happened to see strolling down the street!” “Oh yeah? Well, I…” You get the picture.

It’s easy to imagine the novice scripter hunched over a notebook in the back of the room, scribbling furiously and grinning like an greenhorn prospector who’d just stumbled upon a vast field of fool’s gold. “Wow! This stuff is dynamite! Especially the guy who blew up his wife with a stick of dynamite!”

So goes Drunks, a 1995 film directed by Peter Cohn, written by Gary Lennon, and featuring a whole slew of Hollywood stars eager to Make a Statement.

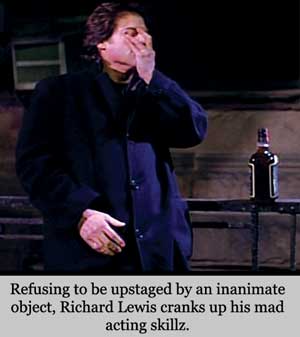

The movie kicks off with the protagonist Jim (Richard Lewis in his first and hopefully last dramatic role) arriving at an AA meeting set in a church basement.

It turns out the designated speaker has been sidelined, so the meeting leader goes to the bench and brings in his reluctant-hero/go-to guy, Jim. Jim is set up as some sort of AA celebrity, a highly-decorated veteran of the Booze Wars. The meeting leader wants “a real war story,” something dark and deep, and after a lot of cajoling, Jim finally agrees.

Our squirmy hero delivers a rambling speech about how he started boozing quite young (it was his father’s fault), then turned to heroin because the booze had lost its power to get him high (he was pounding a quart a day and couldn’t get drunk).

Then he met the perfect woman. She checks him into rehab, gets him straight, then has the gall to die (a sudden brain aneurism) a couple years later. Following a post-funeral binge, Jim has presently been off the booze for eight months.

The crowd eats it up, but the mere telling of his tale seems to have a different effect on Jim. He storms out in a rage, leaving us to get to know the standard stereotypes who remain.

The list includes the neurotic (Amanda Plumber), the hard-as-nails, matchstick-chewing black dude (Howard E. Rollins Jr.), the blue-collar knock-about (Sam Rockwell), the wild child (Parker Posey), the motherly heavyset woman (Fanni Green) and so on.

The list includes the neurotic (Amanda Plumber), the hard-as-nails, matchstick-chewing black dude (Howard E. Rollins Jr.), the blue-collar knock-about (Sam Rockwell), the wild child (Parker Posey), the motherly heavyset woman (Fanni Green) and so on.

The production notes tell us the actors were encouraged to improvise their scenes, which explains why they’re so disjointed and “actor workshoppy.” It also explains why successful writer/actors are a rarity in Hollywood.

The abundance of familiar faces might also explain the aggressive overacting that permeates the film. That spirit of competition I mentioned earlier applies to actors as well, and the cast of Drunks seems caught up in a contest as to who will deliver the stand-out performance. The scenery is chewed with such voraciousness that one imagines the film crew was forced to don those padded body-suits used to train attack dogs.

Right off the bat, Amanda Plumber raises the bar high with a bizarre stream-of-consciousness monologue about wanting to slip her mother (who insists on sharing Amanda’s bed, in the nonsexual sense, we presume) a tab of Ecstasy. Why, and what does has that to do with drinking? Dunno. Probably just something Amanda threw together in her trailer before the shoot.

When it comes to declaring how many days they’ve been off the booze, one mouse-voiced woman coquettishly inquires if she should count the days she was “tied up in a straight jacket.” Which elicits, for some reason, a big booyah from the gang. (She is generously informed she’s allowed to notch up her days in the booby hatch.)

The meeting leader suddenly starts obsessing about “What’s going on with Jim?” and Sam Rockwell resolves to find out.

Which leads us back to our hero, who is bebopping through decadent pre-Disney Times Square to a jazzy beat.

Bebopping is probably the wrong word. Lewis possesses the singular ability of making something as simple as walking down a sidewalk seem as futile and painful as Sisyphus rolling his boulder up the mountain.

The plethora of neon liquor store signs haunts him until he finally surrenders, ducking inside to announce: “Hi, my name is Jim, and I want a pint of bourbon.”

Which he gets. Outside in an alley, however, Jim undergoes a crisis of thirst. He engages the bottle in a rather one-sided argument, but after some profane expository, he wins the debate with a well-polished nugget of AA logic: “It’s the first drink that gets you drunk.”

Which he gets. Outside in an alley, however, Jim undergoes a crisis of thirst. He engages the bottle in a rather one-sided argument, but after some profane expository, he wins the debate with a well-polished nugget of AA logic: “It’s the first drink that gets you drunk.”

Right! Just like it’s the first bite of a sandwich that makes you full, and the first kiss that knocks you up.

Following a hearty farewell (“Fuck you in the ass, you fuck!”), Jim abandons his vanquished opponent on a railing—which must have reconstituted some wino’s belief in the Almighty, if only for a night.

Back at the meeting, we are witness to the first rumblings of a perfect storm of bathos and bad acting. The previous travesties were a mild drizzle compared to what’s coming. The attendees will reel off an entire menagerie of sordid crimes alcohol somehow huckstered them into committing: child murder, heroin addiction, assault, drunken child cuddling, shopaholicism—the works.

I want to die sober, an HIV-positive woman righteously declares. Uh, why?

Back to Jim. We find him at a different liquor store, intent on buying another pint, making one wonder why he doesn’t retrace his steps and make up with the bottle he shouted down. Regardless, he parlays with that fabled but rarely encountered liquor-store-clerk-with-a-conscience. He knows Jim and refuses to sell him liquor because Jim’s a bad drunk. Jim ripostes by shaking up a bottle of champagne, popping it open, and crowing, “Happy New Year!”

That Jim, he so craaaaazy!

After getting tossed out, it becomes clear that Jim is a bad drunk, if only in the sense that he’s bad at getting a drink.

We pop back to the basement to watch Sam and Amanda take turns leaving goofy, heartfelt messages on Jim’s answering machine. Ho-hum.

Back to Jimmy. Third time’s the charm. He manages to purchase a pint without getting in a moral argument with either clerk or bottle. He has a couple of small but dramatic swigs on the way home, which serve to get him loaded. Apparently he’s shed his quart-a-day/don’t-feel-a-damn-thing tolerance. He stops by a downstairs neighbor’s apartment and slurs at the door for awhile. In fact, it appears he is actually begging for sex from the door itself, because his voice is so low he could not be possibly heard from inside.

Upstairs in his apartment, Jim engages in another skirmish with the sauce: he picks up the glass, he puts it down, he makes some faces, then—finally—he works up the gumption to slug down a highball of bourbon in a single go. At last! After all the buildup, Jim begins what is sure to be a wild ride to rock bottom.

Meanwhile, across town, Parker Posey, a self-confessed “strange bird” prattles on about getting married while blacked out (to a guy named Wild Bob, no less), but now resolves to be the “clean and sober” Janis Joplin of her generation. Which is kind of like being the Timothy Leary of your generation, minus the LSD.

It quickly becomes evident that Posey’s character is there to prove you can have plenty of rock-n-roll attitude without the booze, but it comes off with a weird desperation that probably wasn’t intentional.

Amidst her histrionics, in creeps the Token Counterbalance Character. Whew. Thought he’d never show up. It is none other than Spalding Gray (who was known to be a bit of a drunkard in real life), suited up as an affluent ex-hippie. He sits in the back and patiently waits.

Back at Jim’s flat, matters have taken a dire turn indeed. Our fallen hero, for the love of Christ, is getting into the beer. Horrors! Before having a lusty swig, he carefully checks the alcohol content on the side of a can.

“Dangerous!” our veteran boozer declares.

Which is probably the first time, outside of junior high school, that the word “dangerous” has been applied to something that weighs in at 12 proof.

He then contemplates getting kinky with one of his dead wife’s nighties, but thankfully restrains himself.

Back at the basement, we find none other than Faye Dunaway mugging her way through a scene. Fresh from her brilliant and lively performance in Barfly, she’s eager to prove she can play a boring drunk as well. She pulls it off without a breaking a sweat.

Meanwhile, things are improving mightily for Jim. Tanya, a grade-A blonde floozy and owner of the previously propositioned door downstairs, slinks in.

“Fuck the program, man, I just need to loosen up,” announces Jim. No longer full of angst about lost love, he makes out with Tanya, then engages in a hilarious round of dirty talking. But alas, Tanya’s a heroin addict and she needs some dope, like right now. No dope, no sex. She leaves and it’s the last we’ll see of her, but hey, let’s not quibble about dead-end sub-plots. She provided a heaping helping of nudity, and that surely counts for something.

Back at in AA Land, the stories just drag on. Dianne Wiest has her turn, and turn the screws she does. She’s an upstanding doctor who was waylaid by pills (oh, and some booze too). The story doesn’t go anywhere, but that seems to be the fashion.

We find Jim at his old local bar. The drunks and staff welcome him back with open arms, which is a little surprising because Jim is what those in the service industry call “a major asshole.”

After grandly informing the bartender that he will need to gather up every mixologist skill in his repertoire, Jim orders an ultra-complicated whiskey with a beer back. Lest they think him a boor, however, he sets them straight with a witty gem of a toast: “Here’s to everyone and fuck everything!” Jim is back on track.

The Token Counterbalance Character finally makes his move. Spalding starts badly by hilariously stating, “The stories are so real and honest, nothing compares to this in television or most movies.” Uh-huh. Imagine the ingrate screenwriter typing that one up.

He rebounds nicely, however, and goes on to give the only intentionally funny dialogue of the film, loaded with semi-poetic descriptions of the beauty of alcohol.

He doesn’t reckon he’s an alcoholic. But then, he’s not “a sober” either. He’s “a fuzzy” and he likes getting fuzzy every day. He likes beer. He likes boilermakers. He likes to watch them boil and foam up. He comes across as a voice of reason, and the only likable character in the movie, aside from the affable bartender who’s doing a swell job of putting up with Jim.

Jim’s bitching up a storm about “those zombie asshole motherfuckers” back at the meeting. Why, all they do is talk about fucking booze and drinking, but none of them fucking drink!

Amen, brother.

“But fuck that shit,” Jim goes on, “I’m getting loaded tonight.” He buttonholes some poor yuppie who’d popped in for a spritzer, then starts addressing strangers as “fat fucks.” That’s no way to get back in the good graces of the tribe, Jimbo.

Clalista Flockhart finally steps up to the plate and swings mightily. After announcing she’d rather be dead than sober, and that she sure as hell doesn’t need any stares or pity, she has a moment of clarity and realizes she’s in the wrong basement. She was probably looking for the Drinking Totally Rules, So Fuck You meeting. She storms out, but only gets as far as the ladies’ room, where she’s set upon by a weirdly smiling Dunaway, who, as far as I can tell, is putting moves on her.

Dunaway slips Flockhart her number, they embrace, then gaze into the mirror and assert repeatedly how fabulous they are (I’m not making this up, but the actresses evidently did).

Dunaway slips Flockhart her number, they embrace, then gaze into the mirror and assert repeatedly how fabulous they are (I’m not making this up, but the actresses evidently did).

Meanwhile, Jim is trying to score some smack. See? Booze is a gateway to hard drugs. All it takes is a couple hours. He schleps around Central Park looking for his old connection, Felix, but a helpful drag queen informs him Felix is in the hoosegow. Alas, Jim is reduced to scoring from strangers. How embarrassing. But how’s he going to shoot up without a rig? Oh, there’s one! Right next to the comatose junky! What luck!

Cathy (Annette Arnold) is ready to come out of her shell. We’ve been subjected to countless cutaways to her deeply tormented mug since the film started, so you just know it’s going to be angst-tacular.

She has no friends (because she drinks), she has no home (because she drinks), the father of her unborn child has left her (because he drinks). All she wants to do is stop sleeping in doorways (of hairdressers, judging by her perfectly-styled perm).

That downer sucks so much air out of the room that the leader, after a half-hearted “Keep coming to meetings, we don’t drink here,” immediately shuts down the operation.

Jim is wrapping things up as well. He needs a private place to shoot up, so naturally he heads back to the bar. But first he reveals to the bartender that he never really liked his dead wife that much, and their time together was just one big hassle. So, with the underpinnings of his character’s motivational arc neatly sheered away, he does the next logical thing and retreats to a table to cook up his junk.

Before he can get cooking, however, a nosy bouncer rats him out and he gets tossed, sans smack, into the cold dark night, where he communicates his arrival at rock bottom by feeling up a Dumpster.

If you can’t predict the final scene, you need to retake Hack Films 101. Come morning, Jim’s sitting in the back of a different AA meeting wearing a hangdog expression. He wearily announces his alcoholism, then says in 24 hours he’ll have one day of sobriety under his belt.

It’s beyond me why he’s so depressed. So he got a little drunk, acted like an asshole and made out with a floozy. It’s not the end of the world, Jimbo! Hell, a lot of guys would call that a five-star Friday night.

—Frank Kelly Rich