Ever wonder what it would be like to drink in the great watering holes of yore? Well, pack your flask and climb aboard the MDM time machine — your guide Richard English is taking you on a whirlwind tour of the hottest of history’s hot spots.

Ancient Medicine

Compared to the sweeping, 7,000-year story of humans and hooch, taverns (beer halls, bars, ale houses, gin dens, bar-and-grills, call them what you will) are relative newcomers. Getting loaded, however, has always been a popular social activity, so the first two entries are places where the liquor flowed freely and getting hammered was the order of the day, even if they lacked neon beer signs, free peanuts, and 25-cent pool.

The Festival of Dionysos

The Festival of Dionysos

Athens, Greece, 380 BC.

There’s no prettier place than Greece in the springtime. It’s not too hot, everything is green and blooming, and the breeze off the ocean will actually give you a massage.

Each year, Athenians celebrate the arrival of spring with the Festival of Dionysos, a week-long event honoring—how did you guess?—Dionysos, the ever-popular god of wine and theater. The festival features parades, splendid declamations by professional orators, banquets with food enough to render an army fat and sassy, and itinerant philosophers. It culminates with a competition between three of the city’s tragic playwrights, each of whom presents a fully-staged trilogy of works in the Theater of Dionysos, on the south side of the Acropolis. The audience selects the winning trilogy by secret ballot, and the triumphant writer achieves superstar status.

Oh yeah. The Festival also features wine. Lots and lots of wine. Wine by the cup, wine by the jug, wine by the bucket, wine by the cask, wine by the vat. Literally everyone is pouring. And it’s all free, every last dark delectable droplet.

If the speeches, parades and tragedies aren’t your thing, don’t worry, the festival is a city-wide event. The party is happening everywhere you look. People dance and skip and reel through the streets in wine-soaked hordes (rather like the running of the bulls in Pamplona, but with the bulls running from the people). You can drink from a small decorative bowl, like a proper Athenian, or dispense with such niceties, and go for it with whatever vessel is near at hand—a boot, a bucket, your hands, your friend’s hands, whatever. No one will care, just so long as you drink.

If possible, you’ll want to keep your weather eye open for female celebrants. Dionysos is especially popular among the ladies, and the festival is their time to cast aside their traditional roles and exult in unfettered femininity. In Dionysian mythology, the god was accompanied in his roamings by a mob of intoxicated, dangerously devout, female adherents called Maenads. Their primary function was to punish men who got on Big D’s bad side. One such action involved hunting down the misogynist tyrant Pentheus, tearing off his arms and legs, and parading his head through town impaled on a stick. While female celebrants in the 4th Century aren’t likely to actually rip you to shreds, crossing the wrong swarm might still earn you a serious ass kicking. All we’re saying is: have a good time, but leave your “how many chicks does it take to…” jokes at home.

In humankind’s vast drunken history, only a select few occasions compare with the Festival of Dionysos.

The Circus Maximus

Rome, Italy, 150 AD

Ancient Romans are bonkers for live entertainment. Most Roman towns of any reasonable size have public arenas and present a regular schedule of amusements. If you live in Rome, however, there’s only one hot spot to go, and that’s the Circus Maximus.

A massive lozenge-shaped hippodrome (it resembles the Los Angeles Coliseum) on Palatine Hill, the Circus Maximus seats over 250,000 spectators, or about a quarter of Rome’s population. Famous for its chariot races, it is also used for Olympic-style athletic contests, gladiatorial battles, and as a haven for gamblers. The Circus is a great place to make a little extra spending money. You can wager on pretty much any aspect of the spectacle you wish, from a straight bet on the winner, to which appendage a gladiator will lose first.

Drinks abound. The neighborhood around the hippodrome teems with liquor shops, while more aggressive entrepreneurs wander the crowded avenues with pushcarts, bringing liquid sustenance directly to the thirsty populace. Wealthier businessmen have leased spaces inside the Circus’ outer portico, catering to spectators walking to and from their seats. And, just as in any 21st Century stadium, vendors roam the Circus’ aisles hawking stoppered clay jars of beer, mead and wine in varying sizes and qualities. Bring enough coin to enjoy a few jars of the imported Theban beer—it’s renowned throughout the Mediterranean—or splurge on a full jug of Mendalian wine from Greece. As the saying goes: “The gods themselves wet their fine beds on the Mendalian.”

The easy availability of cheap hooch makes for a rowdy crowd. Boisterous spectators hurl epithets at the combatants, and pelt them with rotten fruit, empty beer jars and well-ripened fish. Fights are common, but can usually be diffused with a round of drinks and a hearty toast. Oh, and you might want to keep your money pouch tucked safely inside your toga. Cutpurses infest the throng like fleas on a country ‘coon-dog, and a happy drunk such as yourself will appear an easy target.

Art and Revolution

The late Middle Ages introduced the first proto-taverns. Often controlled by local clergymen who knew how to motivate their flocks, these infant bars were usually little more than a couple of knotty wooden planks and a cask of ale. Thirsty laborers ponied up a penny or two for a quaff from a common-use dipper. The proceeds were returned to the community in the form of church improvements. Many a stone mason could look upon his work and say with pride, “I drank that abbey into existence.”

Independently-operated beer halls came into their own as successful businesses and important gathering places in the 1500s. Apart from certain cosmetic changes and sanitary improvements, they haven’t changed much since.

Here’s a pair of classics.

The Mermaid Tavern

The Mermaid Tavern

London, England, 1599

Souls of poets dead and gone,

What Elysium have ye known,

Happy field or mossy cavern,

Choicer than the Mermaid Tavern? —John Keats

Big changes are afoot in old London Town. For starters, a new queen sits on the throne, Elizabeth I. Her economic policies have created a brand new strata of society—the middle class. Londoners have more expendable income than ever before, and they spend a lot of it on entertainment and booze. Drinks can be had for a pittance. Most people drink ale or mead, as wine is too costly to import and grapes don’t do well in the chilly English climate. Favored entertainments include wrestling matches, bear baiting and live professional theater, a fairly new invention that has reintroduced a kind of fame the world hasn’t seen for a thousand years—the celebrity writer. If you’re looking for a fine place in which to tip a few dozen pots of ale, you need only follow the scribes.

Young, famous, and increasingly wealthy, London’s professional playwrights and poets know how to have a good time. A later historian will separate six of them from the flock and name them the Roaring Boys—Thomas Kyd, Thomas Nash, John Webster, Ben Jonson, Christopher Marlowe and perhaps the greatest scribe of all time, William Shakespeare. Each has his favorite tavern, but most days they congregate at the Mermaid.

Day, night, and in between, if you are drinking, the Mermaid is serving. Find a table near the back of the common room so you can watch the entire scene. Ask any of the comely barmaids for a pot of the day’s best. Don’t try the sausages; they smell funny. Sit back, take a pull of that rich, warm ale and relax. If you grow restless, you can avail yourself of numerous entertainment options. You might gamble with cards or dice, play skittles, bowl, or wager among your friends as you see fit. On a good night, someone might bring in a wild beast (usually from “darkest Africa”) or a horribly disfigured person, and you can take a gander for a penny. If the mood takes you, the room is rife with entrepreneurial ladies, whose favors come in a range of prices. Many of them still have teeth.

Drink all you can afford, but be watchful who you talk to. Elizabethan London is a cesspool of political gamesmanship, and aswarm with spies and blabbermouths more than willing to rat you out for a few pennies. Duels are also commonplace at the Mermaid, as are run-of-the-mill disagreements that turn into ferocious blood-fests. If the Mermaid is your destination, bring your sword. A back-up dagger in your boot won’t hurt either. Bring enough coin to (quietly; just a whisper to the tavern keeper) buy a round for the house. Someone will return the favor. It’s the custom.

The Green Dragon Tavern

The Green Dragon Tavern

Boston, MA, 1773

If you like your drinking establishments steeped in Important Events, make sure you drop in Boston’s Green Dragon Tavern. The Green Dragon is a hotbed of anti-British, pro-independence agitation and intrigue. If you had to name one location as the birthplace of the American Revolution, this might well be it.

Case in point: In December of this year, a group of 50 revolutionaries, dressed as Mohawk Indians, will raid three British ships and toss their cargo into the harbor, an action that will come to be known as the Boston Tea Party. All planning for the raid will happen in the Green Dragon, under the guidance of men like John Hancock and Samuel Adams.

The Green Dragon is largish, as taverns go, with several long common tables in the middle of the room and smaller ones around the perimeter. The ceiling is high, so the room is less smoky than most. Over in the corner, three men play up-tempo tunes on flute, fiddle and drum. The atmosphere is boisterous, but tense, and conversations are tinged with anger. Royalists and their Red Coat goons avoid the Dragon. Their mere presence is enough to instigate a brawl. Only the most dim-witted “king’s man” would reveal his feelings here, not unless he desires a comprehensive understanding of the words “tarred” and “feathered.”

There’s food if you like, but most people are here to drink. The menu lists several kinds of beer, as well as hard cider, whiskey, rum, and perry. No-nonsense serving girls thread their way through the throng delivering tankards and cups. And you’ll keep your hands to yourself, if you know what’s good for you. These girls have friends in high places.

When you first arrive, be cool. Give the regulars some time to get your measure. Then, if you have the means, buy a round for the house; you’re new in town and it’s a good way to get your name known. Join in the drinking, and have all you want. No one here will think less of you for wobbling. Join in the conversations.

Hell, join in the Revolution. It’s the right thing to do.

On The Wild Side

The Entire Town

Tombstone, AZ, 1880

Yeah, yeah, yeah. This is supposed to be a guide to great drinking venues. But when you start wandering the Wild Wild West you discover towns so single-mindedly devoted to getting blasted that they can’t be fully summed up by one or two quality saloons. Topeka, Kansas is one. So is Dodge City. Likewise Amarillo, TX, Central City, CO, and Deadwood, SD. But Tombstone is the shit. It’s the acme, the ne plus ultra of rip-roarin’ western towns.

In the years since Tombstone sprang from the Arizona desert (1877), the town has attracted an extraordinarily bizarre mix of humanity. Before you make a beeline for the nearest saloon, spend a few minutes soaking in the scene:

In the years since Tombstone sprang from the Arizona desert (1877), the town has attracted an extraordinarily bizarre mix of humanity. Before you make a beeline for the nearest saloon, spend a few minutes soaking in the scene:

Nattily attired bankers rub shoulders with hardened killers; renegade Apaches buy shots of fine Kentucky bourbon for wealthy garment merchants; sporting ladies trade beauty secrets with the wives of politicians; grizzled silver miners play checkers with fire-and-brimstone preachers; and cattle rustlers wait in line to see a traveling production of The Pirates of Penzance. On Main Street you can buy the latest fashions from Paris, enjoy a five-course meal, listen to the local brass band, lose yourself in a Chinese opium parlor, try your luck at a faro table, watch a bare-knuckle boxing match, cut a rug in a dance hall, rent a good time in a bawdy house, or wind up on the losing end of a pistol fight.

And you can drink.

There are 300 businesses in Tombstone, give or take, and of these 40 are saloons—The Grand Hotel, The Cosmopolitan Hotel and Hafford’s Corner Saloon are among the better. If, however, you can’t find one that pops your cork, strong drink is available at over two dozen other establishments, including the mercantile, most restaurants, all bordellos, and at least one local church.

People in Tombstone drink whiskey—man, woman, and child. Some places serve beer (even ice-cooled) and wine, but it’s whiskey that stokes the civic furnace. These are hard people—miners, cattlemen, gamblers, thieves—and haven’t the patience for piddling measures. Whiskey is distilled locally and imported from all over the country, so the quality varies wildly. A shot in an upscale joint like the Cosmopolitan might cost you as much as a dollar, but if money is an issue and your health is not, you can buy a bottle of eye-watering rot-gut for a dime. It tastes like kerosine, but so what: three or four swallows will sufficiently numb your throat against such fancy city-boy concerns. Folks say the hallucinations are fun, too.

Tombstone is a dangerous burg. Violence and sudden death lurk around every corner, so kudos to the town council for spending enough money to attract a quality constabulary. The argument can be made, in fact, that never before or since has a more famous, and effective, gang of lawmen patrolled the streets of the same town at the same time. You’ll usually find them in the Grand Hotel bar:

Sheriff Johnny Behan; Deputy Sheriff Bat Masterson; badges-for-hire Buckskin Frank Leslie and Turkey Creek Jack Johnson; U.S. Marshall Virgil Earp; shotgun messenger and occasional Deputy Morgan Earp; Deputy U.S. Marshall Wyatt Earp; and the gambler, part-time deputy and town dentist, John Henry Holliday, known to his friends as “Doc.” Even if their names did not proceed them, you can tell with a single look that these are not men with whom to fuck.

So, check your guns at the sheriff’s office and pick a watering hole. Sidle up to the bar and blow the dust from yer pipes. Mind yourself. Keep your temper on a short tether. Tombstone will treat you about like you treat it.

About.

The Fewclothes Cabaret

Storyville District, New Orleans, LA, 1918

Fine music drifts from the Fewclothes. Only a comparative few have ever heard it before, but within the next decade it will take the world by storm. Some folks call it “jass”—from the jasmine-scented perfume favored by Storyville prostitutes—but to most everyone else it’s jazz.

It is not true, as some claim, that jazz was invented in Storyville. The music grew organically from the city and the people, so locating the exact cradle of its invention is impossible. Storyville can, however, lay claim to nurturing the music during its infancy, and the Fewclothes Cabaret gave it a place to grow. The greats plied their trade here: Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, Kid Ory, Buddy Bolden, King Oliver and that new kid with the hot horn, Louis Armstrong.

Of all the joints a time-traveling drunkard can stagger into, the Fewclothes is probably the most dangerous. You’ll want to go armed. A switchblade or straight razor will fit nicely in a boot or hip pocket, as will a smallish revolver, like a .22. One thing you don’t need is lots of cash. Drinks here are dirt cheap. It’s Drunkard Heaven. Two fingers of gin and a mug of beer will run you 10 or 20 cents. An “over and under” (equal parts gin and red wine) can be yours for a quarter. Ice costs an extra nickel.

And you can drink like a fish, too. All that dancing sweats it out about as fast as you pour it in.

All Grown Up

A few hundred years of tinkering ironed the wrinkles out of the “tavern” idea, and by 1900 owners were free to experiment, to cater to their specific neighborhoods and indulge their personal preferences. By mid-century the word “bar” no longer contained enough information. Bar? OK, but what kind of bar? Answering that question created a new vocabulary: cocktail lounge; dive; brew-pub; sports bar; night club; fern bar; speakeasy; karaoke bar; singles place; comedy club; meat market; gay bar; music hall; neighborhood hangout; topless bar; strip joint; cabaret; dance club; blues bar; bar-&-grill; biker joint; tiki bar; and a thousand other bars with a thousand different themes.

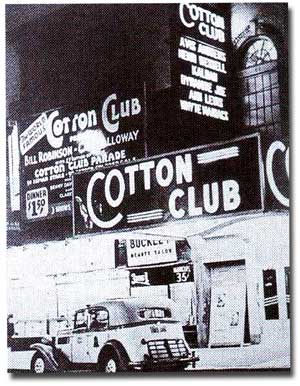

The Cotton Club

The Cotton Club

Harlem, NY, c. 1925

Some people say it’s a speakeasy, but it isn’t. Not really. For one thing, it’s not exactly a well-kept secret; everyone knows where it is. For another, you don’t have to go through the whole password rigmarole to get in. And lastly, it’s never raided. All the right palms have been greased, and some of the regulars are sufficiently wealthy and connected (either to New York’s political establishment, or the Mafia) that only the most foolish Federal agent would risk busting them.

Located at 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue, the Cotton Club was opened by heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, who sold it to Owney Madden, a prominent bootlegger and gangster, in 1923. The C.C. is a favorite destination for celebrities like Mae West, Jimmy Durante and George Gershwin. Duke Ellington leads the house band while tap dancer Bojangles Robinson and singer Ethel Waters thrill the house. Between performers, patrons hit the floor, dancing the Tango, the Black Bottom, the Charleston and other hot dances from Flapper-land.

Ah, the flapper. The Cotton Club incubated that icon of female intoxication. They’re easy to spot, what with their short, spangled skirts, bobbed hair and scarlet lipstick. They openly, some say brazenly, smoke cigarettes and knock back cocktails. When they dance, their milk-white arms and legs are a tantalizing blur of scandalously bare flesh. (That sporadic flash of silver is the gin-flask gartered to her thigh.)

Owney Madden’s patrons expect top-shelf libations, and he comes through in spades. He runs his bootlegging operation right from the Club, and skims the best product off the top for sale to his guests. It’s real liquor, too, not some nasty turpentine cooked up in a Yonkers pig-barn. No, this is whiskey from Ireland and Scotland, sneaked into the country from Canada, and rum, smuggled up from Cuba through secret ports in Florida and Louisiana. About the only visible hint of Prohibition is that your drinks arrive in porcelain tea cups.

Chances are slim that any violence will erupt during your visit, but it pays to keep your eyes and ears open. Owney Madden hasn’t risen to power without pissing a few people off and, sadly, two of the fellows he has irritated are the mafia kingpins Dutch Shultz and Lucky Luciano. Like it or not, Dutch and Lucky (and their armed goons) are fixtures at the Cotton Club. So are their mistresses, so you might want to exercise a little caution before buying a drink for that gamine lass seated by herself near the dance floor.

Otherwise, feel free to indulge in all that the Cotton Club has to offer. If you can’t manage to have a good time here, it’s only cuz yer dead.

Rise of the Speakeasies

New York City, NY, 1920-1930

Prohibition is the law of the land, not that you can tell by looking around New York City. The misbegotten law designed to eradicate drinking has increased the activity by 200 percent, and has called into existence twice as many drinking establishments as it has closed. Such places are paradoxical; “secrets” that everyone knows. All you need is the password. Whisper it to the guy at the door and go on in. But do it quietly, friend.

Speak easy.

Even with a time machine, hitting all of New York’s speakeasies would take a really long time, and, other than being able to brag that you saw them all, would be a waste of time. There are literally thousands to choose from, but the majority are nameless burrows in damp cellars and squalid back rooms, where you are more likely to be poisoned by bad liquor than have a good time. You’ll be better off sticking to those operated by bootleggers and gangsters. Say what you want about their business habits and questionable moral indulgences; they know how to make their guests happy. Here’s a (very) short list of starting places.

Jack and Charlie’s 21 Club

Owned and operated by cousins Jack Kreindler and Charlie Berns, this is the quintessential speakeasy. They have been running speaks for years, relocating because of federal harrassment and changing names each time. Their first club, called the Red Head, opened in Greenwich Village in 1922. It moved to Washington Place in 1925, and became the Fronton. Less than a year later they moved yet again, uptown this time, to digs on West 49th Street, and called it the Puncheon Club, the most successful incarnation to date. In 1929, they were forced to move again, this time to make way for the construction of Rockefeller Center, but it proved to be their final change of address, and Jack and Charlie’s 21 has been here since.

The cousins have learned a few things over the years about dodging federal agents, as is made plain by the security systems in place at 21. The instant they get wind of a raid, they trigger an array of levers and pulleys which tip the liquor shelves back into the wall and replace the bottles with nick-knacks. Simultaneously, a chute opens at the end of the bar and all glasses and bottles are swept down it, into the sewers below. The evidence is gone by the time the lawdogs arrive. They have also constructed a secret wine cellar in the basement of the neighboring building, #19. It’s accessed from the basement of #21 through a massive two-ton door that’s disguised to blend in with the rest of the brick wall. The door is unlocked by poking the tip of a meat skewer into a hole and activating a switch inside.

The club is open 24-7 which makes it a favorite haunt for writers like Damon Runyon and William Saroyan. Rumor has it that many of Runyon’s memorable characters are based on people he knows at Jack and Charlie’s. It also attracts its fair share of Mafia types and show business people.

Perched somewhere between fashionable and dumpy, Jack and Charlie’s 21 is a place to have fun and get a little rowdy.

300 Club

Located at 151 W. 54th Street, the club is owned and operated by its founder, Texas Guinan. Best known as the original silent movie “cowgirl,” Ms. Guinan wanted to parlay her Hollywood money into a Texas-sized fortune, and when Prohibition hit she knew she’d found just the license to print money she’d been looking for.

The 300 Club provides decent drinks, served by adorable, pouty-lipped hostesses, and vaudeville-style entertainments, interspersed with performances by leggy chorus girls. Ms. Guinan herself gets the shows underway, barking her trademark greeting: “Hello, suckers!”

The 300 isn’t as stylish as some speakeasies, but it’s better than most. It’s also a bit more flagrant than most. Your average speak’ makes at least some effort to avoid the hard gaze of the law by using passwords, cracking down on overly rowdy behavior, and using lookouts to warn of legal encroachment, but not Texas Guinan. When the feds raid her club she explains, in tones of shock and outrage, that she is but a humble purveyor of tea and soft drinks, and that any demon rum found on the premises must have been sneaked in by “lower elements.” She rarely fools anyone, so depending upon when you choose to visit you’ll find the club at 310 W. 58th Street, or 203-211 W. 54th Street.

A final note for trivia buffs: Whoopie Goldberg’s character on Star Trek: The Next Generation, the bartender Guinan, was named after that little darlin’ Texas Guinan.

The Stork Club

The Stork Club

Several rungs higher up the style-and-glamour ladder than the 300 Club, The Stork is the brainchild of Sherman Billingsley, a transplanted grifter and bootlegger from Oklahoma. A host among hosts, Billingsley greets each table personally, often staying to chat for a minute or two. Celebrities and big spenders receive a complimentary bottle of champagne, opened and decanted at their table with a flourish by Billingsley himself. Gossip columnist and infamous barfly Walter Winchel says The Stork is “the New Yorkiest Spot in New York.”

The entertainment is the best money can rent, and the drinks are mixed by an experienced corps of resident mixologists. They recently got together and penned one of the best-selling drinks guides of the decade: The Stork Club’s Guide to Mixed Drinks.

You won’t get by cheap at the Stork. Take the money you’d usually bring to a ritzy nightclub and triple it. It costs ten bucks per person in 1920s dollars just to walk through the door. That’s about $150 in 2007. And you’ll want to behave yourself. The Stork is about chic, about elegance, and sudden outbursts of drunken rambunctiousness are not tolerated. The club’s enforcers are known all over town for their size and unwillingness to heed excuses.

Claudio’s

Located on a waterfront pier, this is a place to cut loose, if that’s your thing. About one rat shy of divedom, Claudio’s is a place to drink. There’s an upright piano in the corner and, occasionally, someone to play it. On a good night you can drink “real” liquor. There aren’t many good nights. It’s all cheap, though, so come on in.

Claudio’s is also notable for its method of dodging federal raiders. There’s a trap door behind the bar that opens right onto the water. At low tide, they keep a small boat under there and, at the first sign of a raid, drop all the hooch in it and paddle away. If it’s high tide, the contraband goes straight in the drink, to be retrieved later by “divers” with ropes tied around their waists.

The Smart Set

The Algonquin Hotel

New York City, NY, 1926

“The Gonk” as it’s known to its regulars, differs from those places described so far in one important respect: patrons bring their own booze. But don’t let that dissuade you from visiting. Lots of Prohibition-era clubs operate the same way, providing set-ups and allowing customers to do their own mixing. And besides, buying your own bottle is, as always, cheaper than paying marked-up house prices. Hip flasks are popular accessories among regulars. Andspeaking of the regulars, they are the main reason for an outing to the Algonquin.

A who’s-who of New York’s literati, they call themselves the Algonquin Round Table and meet daily for several hours of laughter, witty banter and scathing gossip. Among the notables are playwrights Marc Connelly, Robert Sherwood and Edna Ferber; journalists Alexander Woollcott and Ruth Hale; humorists Robert Benchley and George S. Kaufman; New Yorker editor Harold Ross; actor Harpo Marx; and theater critic Dorothy Parker.The Round Table is the nuclear reactor that powers New York’s smart-set.

A who’s-who of New York’s literati, they call themselves the Algonquin Round Table and meet daily for several hours of laughter, witty banter and scathing gossip. Among the notables are playwrights Marc Connelly, Robert Sherwood and Edna Ferber; journalists Alexander Woollcott and Ruth Hale; humorists Robert Benchley and George S. Kaufman; New Yorker editor Harold Ross; actor Harpo Marx; and theater critic Dorothy Parker.The Round Table is the nuclear reactor that powers New York’s smart-set.

If you go, bring your A-game. These are lettered, quick-witted people, who do not suffer fools, and among whom a sharp put-down will live on for years. And yet, if you value intelligent drinking companions, you’ll be hard-pressed to do better than these.

Cocktails at Nine

Toots Shor’s

New York City, NY, 1950

Bernard “Toots” Shor’s place is among New York’s most famous establishments. It began life as a speakeasy during the waning days of Prohibition, but took off in the years that followed. Shor opened his doors to celebrities and regular guys both, with the emphasis on “guys.” Women aren’t allowed, not even on the staff. As Shor likes to say: “Booze, not broads!”

Shor likes to refer to himself as a “saloon keeper,” and honors the tradition well. He is buddy, priest and bodyguard to the many famous faces who call his joint a home away from home. He goes out of his way to make sure his better known guests get to enjoy their drinks without being pestered by autograph-seekers, and even the many reporters who flock to the restaurant know better than to bug a celebrity without getting the go-ahead from Toots first.

Shor likes to refer to himself as a “saloon keeper,” and honors the tradition well. He is buddy, priest and bodyguard to the many famous faces who call his joint a home away from home. He goes out of his way to make sure his better known guests get to enjoy their drinks without being pestered by autograph-seekers, and even the many reporters who flock to the restaurant know better than to bug a celebrity without getting the go-ahead from Toots first.

Most of the newspapermen are sportswriters, from all the New York dailies—grisled, stogie-chomping veterans of the golden years. Shor himself is a rabid baseball fan, and if he isn’t behind the bar you’ll likely find him at a table drinking with the likes of Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle. Movie stars and entertainers usually pop by Shor’s when they’re in the city. Frank Sinatra’s favorite stool is kept empty in case he comes in, and Jackie Gleason is a regular.

One story (maybe true, maybe not) has it that on an especially boozy Saturday night Mickey Mantle bet Jackie Gleason that the comedian couldn’t outdrink Toots. Gleason is one of the best drinkers ever, a pro, and naturally agreed to the wager at once, secure in his time-tested abilities. When the contest was over Toots went back to work, leaving Gleason in an unconscious heap on the floor.

You’ll like Toots Shor’s. It’s a dive’s dive. A joint among joints.

The Tropicana

The Tropicana

Havana, Cuba, 1953

If you are looking for posh, for glamour, for a place to get plowed without wrinkling your tux, make the Tropicana your next destination. It opened in 1939 on several acres of land in Havana’s stylish Marianao neighborhood, on the lush estate of Guillermina Pérez Chaumont. Latin impressario, Victor de Correa provided the entertainment and designed the shows, while Rafael Mascaro ran the attached casino. The American businessman Martin Fox bought it in 1950 and arranged for the construction of the famous Arcos de Cristal, a series of concrete arches and glass windows over the stage.

Heralded as “Paradise Under the Stars,” the Tropicana is the showplace of pre-Castro Cuba, a favorite destination for American movie stars, captains of business, politicians, and Mafia dons. Alfred Steele, president of Pepsi Cola, owns a villa nearby. Ernest Hemingway, Frank Sinatra and Jackie Gleason are fixtures, as is French cabaret star Édith Piaf. The nightly stage show is a true spectacle (Las Vegas learned everything it knows from the Tropicana), with huge production numbers featuring hundreds of singers and dancers, interspersed with sets by homegrown superstars Xavier Cugat and Carmen Miranda, and imported American headliners like Dizzy Gillespie, Josephine Baker and Rosemary Clooney.

If you plan to visit the Tropicana, you should be prepared to spend some money. But you should also be prepared to have the time of your life.

The 500 Club

Atlantic City, NJ, 1958

Paul “Skinny” D’Amato’s club defines 1950’s cool. He isn’t part of the Rat Pack, but was central to its creation (rumor has it he taught Sinatra the coolest way to hold a drink and smoke a cigarette), and his most recent stroke of genius, the team of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, is blowing the roof off box offices across the country. Gambling isn’t legal in Atlantic City. Yet. It soon will be if Skinny gets his way. In the meantime there is the 500 Club’s elegant back room, a secure hideaway where high rollers bet lavishly on craps and blackjack. Only serious gamblers need apply. A touch of wealth won’t hurt either.

Out in the main room, Nat King Cole is half-way through his first set. Elizabeth Taylor sits with her agent at a corner table, her amazing violet eyes glittering with daiquiri fire. At one end of the bar Milton Berle cracks jokes while Zsa Zsa Gabor howls with laughter. Down at the other end, sitting alone with a double scotch in his hand and a Cuban cigar clamped between his teeth is Chicago Mafia kingpin Sam “Momo” Giancana, probably in town for a meeting with the Gambinos. Everywhere you look, your eyes fall on beautiful women and handsome men. Even the cocktail waitresses, cigarette girls and bartenders are distractingly gorgeous.

The 500 Club is the hippest joint on the East Coast, and the definitive 1950s cocktail lounge.

So there you go. A few fun places to visit when your turn on the time machine rolls around. As far as such a compendium goes, we’ve barely scraped the foam off the glass. There are thousands of others. But don’t fret, we’ll get to them in due time. Until then, give your usual hangout a break this evening and go someplace you’ve never been. You never know what you might find. For all you know, the Next Great Bar might be right around the corner.

(Note: The Author is indebted to the works of Edward Hyams, Walter F. Otto, Liza Picard, Judith Cook, Casey Terfertiller, Marion Meade, Ken Burns, Jonathan Van Meter, Grace Anselmo D’Amato, Rosa Lowinger & Ofelia Fox and Edward Behr.)