Do you remember your first drink?

I know, I know—asking an anonymous, career drunkard if he or she remembers anything is, necessarily, something of a stupid question. There are entire years I don’t remember; I still feel like I might’ve turned 21 yesterday. But the first drink—aye, that’s an indelible memory, your own personal “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.” For the night of your first drink, God willing, was the night you cut your own leash, took your last vestiges of pastel-colored, soft-edged, Fisher-Price childhood and set those sons of bitches aflame. And then you beat your breast and bellowed, announcing to the whole world within earshot, “I’M ALIVE! I’M AN ADULT! AND I’M DRUUUUUNK!”

Let me tell you about my first drink.

I was 16 years old, dull and sober as a pregnant sow, having spent all the previous years of my life swearing to no one, and to no end, that I would never, ever succumb to the evils of alcohol. Folly most foul, I thought, and for most of my childhood, I was driven against it. Who knows why. My parents didn’t drink, I wasn’t supposed to drink—drinking must be bad. So I’ve always been a peculiar kind of proud that this moral foundation I’d grown up in eroded so quickly, and with such aplomb. At 16 I was sober; by 18 I was scoring nine out of ten on Internet tests with titles like, “Are You an Alcoholic?”—by then, the only A-grades I was making in anything.

I grew up a weirdo shitkicker in the grassy countryside of northeast Oklahoma, a patch of the globe that strikes me now, sentimentally, as too easy to criticize, but difficult to defend. The place is home and haven, like most of vanilla America, to an enduring sense of existential ennui, where the main domestic product is a listless lack of purpose. It’s an odd, unsatisfying place to be a teenager, growing up almost comically safe, with always nothing to do. They have this same problem in, say, Alaska, or the upper Northwest Territories of Canada, just to a much more dramatic extent—you can imagine how much drinking they get done up there.

Anyway, you know what they say about idle hands. They are Agents of Sin. Also, they shoplift things.

The scene is a balmy summer night, in a parking lot on one side of my hometown’s only commercial street. I was with three friends, in two cars, myself by far the youngest. Across the street were two stores—the Wal-Mart and the liquor shop. The goal of the night was simple: we wanted to drink. Our plan—our first plan, plan A, all the way—was also simple: robbery.

I mean, how hard could it really be?

In his book Getting Wasted, the sociologist Thomas Vander Ven defines drunkenness as “a process, an arc, an evolution of events starting when one contemplates drinking, continuing down a crooked path of consumption stops and starts, and ending some hours later.” He defines it as an adventure, a journey. Drunkenness as the story of a night, rather than a biological state. Now, professionally, he was strictly studying college students—a class of drinkers who are, in significant numbers, pre-21. Children, idiots, many would say, adults in name only that know nothing about the world, about risk, or their own mortality, but think they just might know it all. Such mindsets are, of course, holdovers from adolescence, adolescence itself simply a step removed from childhood. So if the act of drinking is such a to-do for college students—a whole arc, with twists, turns, and many stories—then imagine what an adventure it must be for actual children, having to find ways to weave all this rebel shit around curfews, parents, and seven-hour school days. Better yet, don’t imagine. Remember.

One of the things I feel like none of us realizes about the earliest days of our drinking is that, apart from discovering the World’s Greatest Pastime, we’re getting up to things that we’re never going to do again. A lot of this has to do with naivety, innocence, and idiocy. Things like drinking warm McCormick vodka in a house full of ice and orange juice, or trying desperately to figure out how to make these Jell-O shots set before Joey’s dad comes home—Guys, seriously, I think we used too much Everclear, it’s not setting, we’re never going to be able to move all these, oh my God we started a small fire.Y’know, joyous memories of discovery and growth. But then there are theother things we were inclined to do—criminal, immoral, and gross. Recall, for instance, the last party you attended. Did its progression, with any resemblance, follow these steps?

- Wait, for days or weeks if necessary, for a house’s lawful occupants to leave their home unguarded for a single night.

- Go to this house. Invite over 2, 10, 20 people.

- Proceed to party. Who lives here, again? To hell with them. Break things, steal liquor, search all cabinets and drawers thoroughly for controlled substances. See if you can open the safe. Oh shit, guys, look: we found a gun.

- Come outside! Paul’s gonna lick the electric fence!

- Taco Bell.

- Have sex in every bed, vomit on every surface, pass out somewhere in the general neighborhood.

- Leave at sunrise. Never tell the people who live here what you’ve done. Keep it a secret for the rest of your life.

Divorced from context, this is essentially criminal insanity—especially the Taco Bell. Imagine a group of grown-ass grown-ups having this kind of night. The image is sad, and scary. (Which is not to say, still, that I wouldn’t go to this party—I mean, come on.)

Dammit, I’m just gonna say it—there was magic to my teenage drinking, and I bet it was special for you too. Those, oh, halcyon days when every party was an adventure, every drink a calculated rebellion, every successful night an implicit testament to you and your allies’ grit, persistence, cleverness and daring. For as kids, our drunkenness—our arc—started well before we had beers in hand, recall. First, there was the daunting and unpredictable challenge—the bare, basic thrill—of acquisition.

Perhaps you had it differently, but for me, for my people, our nights began with nothing. We had no stores or stockpiles, at least not enough for more than a party of one. We left home on Fridays hopeful, but hardly certain, that we’d end the night in our cups. We failed, and often, but on other nights we found the loopholes, and threaded them flawlessly. Nothing tasted sweeter than success. The challenge, the anticipation, was itself intoxicating. Other peoples’ older brothers, crazy uncles, townie strangers—how did you get it? You must have had a scheme, or been privy to someone else’s. Unless your family just gave it to you, in which case…I don’t know, that sounds like kind of a saddening childhood. (Oh, so you were the one with the Cool Mom and the Party House!) If you grew up like I did, in a thoroughly not-college town where the youth leave and the retired return, then it wasn’t always easy to find a comrade of-age or a helpful bum to buy your booze by proxy. So if you grew up like I did, you probably stole it.

There were, of course, lots of ways to do this.

The beginner method—stealing from your parents—rose from, I suppose, convenience and opportunity. Like I said, I never did this. Somehow, I’m the product of two conscientious abstainers. So this is a practice I only ever heard about, not that I feel I was missing much. A sip here, a can there. I remember being so disappointed, so offended by my friends that did this. I tsked so hard, like a judgmental little baby. Dark times. Boo me.

The next logical step was the classic brute force method—the grab and dash, the wreck and run. This one took some balls, no matter what. In my neighborhood, it was a job for the small and swift—and size did matter, because a successful escape invariably involved a daring leap into the trunk of a getaway car. I remember one story, this kid named Ricky—God, he was great at this. I wasn’t there for this one, but word was that one night he pulled off this heist in service of himself and some friendly football players, big guys, practically grown men.

They met no trouble—Ricky was in, he was out, and it was back to home base, where the drivers popped the trunk, tasting victory already, to find diminutive little Ricky, curled up and cozy around one six-pack of Busch. This was intolerable, so back in the trunk he went. The first time had been easy; no one had even seen him. He wasn’t so smooth the second time. Oh, they saw him. But he still escaped. If I’m remembering right, the last thing he heard from inside the trunk before the tires started squealing was someone behind him, shouting distantly, “Hey, some skinny girl just stole y’all beer!”

Casual crime, committed without a second thought. These were the methods we adopted. All morals aside, I would never do this now. (What’s that? Steal a 30-pack? Sir, I am a goddamn adult. I have a salary and a criminal record. There are stakes now. I’ve got a life to lose.) So this is not advocacy I’m doing. It’s just a matter of fact.

Of course, you’d have to be an idiot to think that this high-visibility method of thievery was at all sustainable in a town so small as ours, so we got clever. We plotted in classrooms, traded tips and tricks, cased stores like real-life criminals. We had classic plays. “Dropping the Nachos” meant a two-man job at a gas station, which worked by having one guy head in alone, make a mess—by, say, dropping a plastic tray of nachos—thereby providing a distraction for the second guy to sneak in, grab beer and get out. The “Cooler Switch” was a Wal-Mart heist, accomplished by coordinated teams working surreptitiously to fill the largest cooler we could buy with bottles of booze we legally couldn’t—a classic smuggling scheme, made extra hilarious if you immediately returned the empty cooler. (Shout-out to Mary: that was impressively brazen.)

But it was all brazen, all bold, all reckless. A lot of it was ugly. A lot of it was wrong—like too much drunk driving, or the crying, oh God, the crying. Not all of these memories are good, and not everything we did is defensible. But it all happened. We all did it, the good shit and the bad, before our drinks were even legal for us to possess, before we’d even thought about growing up.

I’ve often wondered what evolutionary purpose was served by the phenomenon of adolescent recklessness, historically, in our far back, animal pasts, before the days of Bacardi 151. Maybe it was how we were moved to leave our nests and approach the world, chests thrust out and boasting. Or maybe the teenagers were in charge of finding out which plants and berries horrifically killed you, and which ones got you high. Someone had to do it.

Practically in spite of myself, sometimes I cringe today at the things I did while teenaged and wasted—but at the same time, I’m glad they happened, and I’m glad I got away with it. I’m old enough now to recognize that was never a guarantee. Even the ugly memories are good now—little snapshots from some whirlwind years I know I’ll never live again, when my idea of a good time was a long walk down country roads at night, drinking warm beer from a friend’s backpack. Before I had taste, or the ability to realistically cultivate it.

Those are my memories, and they are magical, and you have yours, and they are too. But magic like this is hard to sustain, and it’s probably not a good idea to try. But no matter how many drinks we have, the memories of our firsts are never going to fade, not really. In a way, they’ve ruined us. Never again will we experience parties so thrilling, even as we grow and get better at throwing them ourselves. The camaraderie we felt while plotting out nights with friends, our fingers crossed, will be rare to recapture in our lives, and if we live a hundred years or more, we’ll again never taste drinks so sweet as the ones that got us started down this teetering path we’re on.

Which reminds me—my first drink. So there we were, the four of us, sizing up our targets. The plan was for us to split up. Two of us would hit the Wal-Mart. Meanwhile, me and my buddy Baker would break into the liquor store, through the back. It was closed for the night. I mean, how hard could it be? It looked easy. It all did—it was a good plan, this two-pronged assault. (This was, like I said, the very beginning of my criminal career; at this point in my life, I’d never stolen a thing.)

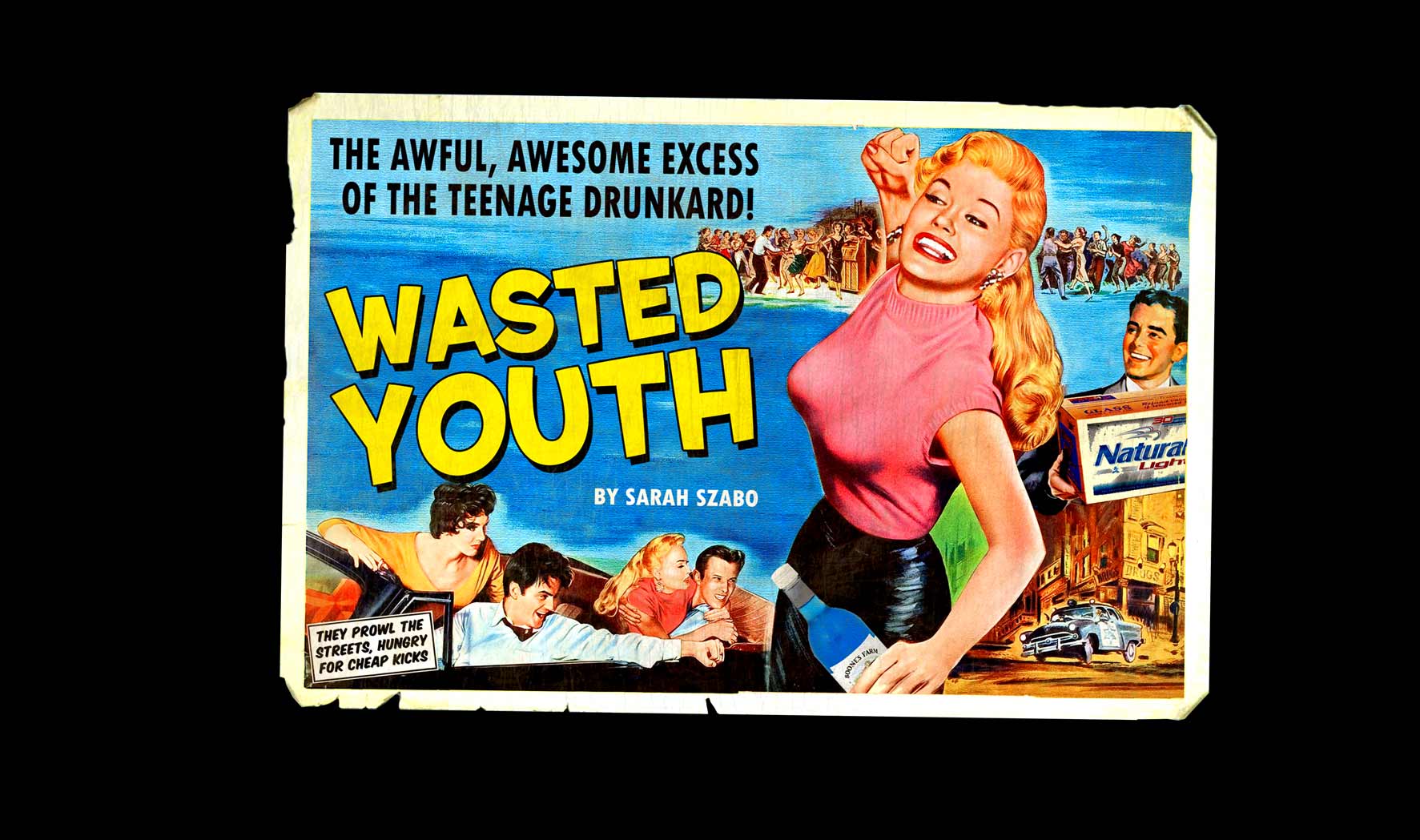

Nor did I, that night. Baker and I stopped at the store’s back door, obviously not intending even a little bit to actually try anything. We chickened out. The other two did not. And their haul, stuffed into a black backpack and carried out the front door like it weren’t nothin’? Why, it was a bottle of Boone’s Farm Blue Hawaiian, and a 12-pack of what is now, to me, an old familiar foe—Natty Light.

Now, like I said, this is Oklahoma, and one of those things about it that I find impossible to defend are its arcane liquor laws, which dictate, among other things, a maximum alcohol content of 3.2% by weight for everything sold chilled in, say, a Wal-Mart. (These laws should also explain my friends’ questionable beverage selection.) At the time, I did not know about these limits. But at the time, I wouldn’t have cared.

Proud, excited, full of mirth and laughter, we drove from the main drag to the outside of town, into the hills, where we hopped the fence of some massive property, and began to drink like . . . well, we drank like children, dancing in the light of the full moon and the brilliant stars, trespassing in some stranger’s field.

Someone passed me the Boone’s Farm, its seal unbroken ‘til it met my grasp. I put the bottle to my lips, tipped it up and felt myself cross a threshold. I closed my eyes. Just like that, a part of my life, one aspect among many, came to its end and left me. Another part came to life, sprung nascent, thin and mewling, from a bottle of Boone’s Farm Blue Hawaiian.

I drank the whole bottle.

I shotgunned my first beer.

And then I threw up.