The Pirate Queen of Ireland

The Pirate Queen of Ireland

Grace “Grania” O’Malley was born around 1530. She was the daughter of Dudara “Black Oak” O’Malley, a powerful Irish chieftain who ran dozens of ships in a herring fleet. Just before Black Oak died he arranged a political marriage, giving fifteen-year-old Grace as a bride to Donal-an-Cogahaidh (“Donal of the Battles”), a son of the O’Flaherty clan. The marriage ended 100 years of animosity between the two clans, and created as powerful a political alliance as Ireland would know for another few hundred years. The story might have ended there if “Donal of the Battles” hadn’t almost entirely failed to live up to his name. Donal was a bad sailor, a bad fisherman, a bad clan leader and, woe be unto him, a really bad warrior. Better names for the man would’ve been “Donal Who Couldn’t Hit the Ocean with a Rock,” or “Donal of the Rapidly Sinking Boat.” He was mortally battle-axed while trying to take an island fortress called Cock’s Castle, and Grace was left a widow with three kids to look after. Irish law wouldn’t allow Grace to be named the Chieftain, so she allowed her uncle to assume the post and ruled through him.

Her first act as the de facto Queen of the Irish Sea was to assemble her father’s fishing fleet and set sail to earn wealth and respect as a pirate. Years of sailing at her father’s side had left Grace with an intimate knowledge of the coves, reefs and currents around the British Isles, and she attacked those Isles, stealing and burning with impunity. Almost immediately she attacked and took command of Cock’s Castle where her poor oafish Donal had bitten the dust. She didn’t lose a man.

Anyone, male or female, raised by a hairy Irish chief called Black Oak, would surely learn how to drink, and Grace took to the craft with relish. Her father had instilled her with an uncommon thirst for all the poteen (whiskey) she could get her bonny-wee hands upon. Even though custom would not allow Grace to be called Chief, Irish women were allowed to drink as much as they chose and were permitted — nay, expected — to join the men-folk in battle.

Alcohol (and its key ingredient, grain) was also right at the top of her list of good things to steal. Sure, grain was useful for making bread as well, but alcohol was as much a part of clan life as bread, as was typical in just about any pre-industrial society you care to name. After every successful raid, Grace doled out the hooch and led the toasts at banquets that sang on ‘til sun-up.

Some years after Donal-the-Useless croaked, Grace married the chief of another powerful clan, a fellow called Richard-in-Iron because he always wore a chain mail shirt. Richard gave Grace a son, whom she named Tibbott-ne-Long (“Toby of the Ships”). She gave birth to the boy aboard her flag ship, abating her birth pains with whiskey, as was the custom.

Less than twelve hours later Grace’s ship was attacked by a Turkish corsair. Her men gave a good go at fending off the Turks, but were outmanned and outnumbered, and sent word below to their captain that all was lost. Grace handed Tibbott to a servant, drank several long swallows from a bottle of whiskey, wrapped a blanket around herself and entered the fray. The Turks stared wide-eyed at the sight of Grace storming from the hold, a pistol in each hand, her red hair billowing wildly in the wind and smoke. She fired both weapons point blank into the Turkish sailors, drew a sword from her belt and screamed: “Take this from an infidel hand!”

Grace’s ferocious arrival turned the tide of the fight. She put such a fright into the Turks that they fled back to their corsair, with Grace’s men foaming at their heels. An hour later Grace was the owner of a fine corsair and a slew of Turkish captives, whom she hanged at dawn the next day.

The party that followed echoed from the very heavens.

Grace lost none of her fire as she aged, eventually running afoul of Queen Elizabeth’s navy. She was arrested for piracy, but petitioned the Queen for leniency in such flowing and complimentary prose that something stirred in the Queen. She summoned Grace for an audience behind closed doors, at the end of which Grace and all her men were released and given property along the coast of Ireland. Elizabeth also knighted Grace’s son, Tibbott, and he became Sir Theobold Burke in 1603.

The same year his mother, Grace O’Malley, the Pirate Queen of Ireland, died.

Not bad work for a pirate and a drunkard.

The Wild Women of the Caribbean

A hundred or so years after Grace O’Malley turned Ireland on its ear, a pair of other ladies achieved equal fame in the Caribbean Sea. Their names were Anne Bonny and Mary Read.

The two firebrands were born about the same time in the late 1600s, Mary in England and Anne in Ireland, each to unfavorable family circumstances. Both were illegitimate daughters of household maids serving (in more ways than one, apparently) wealthy landowners, and their out-of-wedlock status caused their high-born sires concern. Each was sent away, Anne to the Carolinas in the American Colonies, and Mary to France where she would be trained as a serving woman.

Anne and Mary, however, had other ideas about their futures, and banishment into a life of servitude was never part of the plan. Each escaped her situation by dressing up as a man and disappearing into the countryside. Anne slowly made her way to New Providence in the Bahamas, while Mary traveled to Flanders and enlisted as a cadet in the Flemish army, where she would win several medals for bravery in combat. When the fighting was over, Mary doffed her male togs and married a fellow soldier. They opened a tavern in Flanders called the Three Horse Shoes. Sadly, her husband died soon after of influenza and the tavern business lost its allure. So, Mary once again traded her skirts and curls for pants and short hair, and set sail for the New World, landing a few months later in New Providence.

Anne and Mary, however, had other ideas about their futures, and banishment into a life of servitude was never part of the plan. Each escaped her situation by dressing up as a man and disappearing into the countryside. Anne slowly made her way to New Providence in the Bahamas, while Mary traveled to Flanders and enlisted as a cadet in the Flemish army, where she would win several medals for bravery in combat. When the fighting was over, Mary doffed her male togs and married a fellow soldier. They opened a tavern in Flanders called the Three Horse Shoes. Sadly, her husband died soon after of influenza and the tavern business lost its allure. So, Mary once again traded her skirts and curls for pants and short hair, and set sail for the New World, landing a few months later in New Providence.

It was about this time that the ladies made the acquaintance of the notorious pirate Calico Jack Rackham, and joined his crew. They were still pretending to be men at this point since women on board sailing ships were about as welcome as Rob Zombie at an Up With People show.

While they may have been pretending to be men, there was nothing pretend about their on-ship abilities. They were first-rate sailors, able to scale the rigging as adroitly as the spryest male member of the crew. Pirates were known to use the occasional naughty word, and ribald jokes and stories were the order of the day. Anne and Mary were experts at these endeavors as well. Their colorful use of the English language would regularly bring a blush to the cheeks of the hardest seaman. Above all, though, Anne and Mary were excellent pirates, attacking prizes with as much bloodlust as Calico Jack would allow, and often horrifying their male fellows with their dagger and pistol work.

Pirates were terrific drinkers. Aboard Calico Jack’s ship, drinking was done around the clock and our ladies were a cut way above their mates in their ability to put away rum. Anne carried a leather flask of the fiery stuff at her hip for easy access. Mary liked to take her’s straight from the keg with a water dipper. No other member of the crew, Calico Jack included, could match their skills at wrist-raising. Regular drinking contests took place during the hours of boring downtime while at sea. Anne and Mary won so often the men conspired to ban them from the competitions. One of the more vocal pirates said it was unnatural for two men to drink as our ladies did, and went on to hypothesize they were somehow cheating. Mary, the slightly more volatile member of the duo, took offense and challenged the man to a duel. He accepted the challenge and Mary accepted his surrender less than a minute later. Mary stood over the man and drank several dippers of rum before challenging him again. Surely he could best her this time, as she was drunk and he sober. Alas, she kicked his ass again, much to the delight of Anne and the other pirates.

On the rare occasion when Calico Jack’s ship put into port for supplies or repairs, the ladies continued their masculine charade because it allowed easy entrance to the taverns crowding the Caribbean ports. In the style of their male counterparts, Anne and Mary drank, dueled and fought their way from one tavern to another, guzzling rum ‘til dawn’s early light.

The fact that Anne and Mary were not only the best sailors on Calico Jack’s ship, but also the best drinkers, is illustrated by a single story.

The crew was in port when they got wind that a squadron of English ships was on the hunt for them. They set sail at once, looking to hide among the many hundreds of uncharted islands peppering the Caribbean. Since they were on the run and not searching for prizes to seize, they took to drinking from the new kegs of rum they’d purchased while ashore. Someone had a squeeze-box and the sailors danced and sang for hours under the tropical sun. Things were so lively that no one noticed the arrival of an English ship. Taken by surprise, the crew cowered in fear. Most of them, anyhow. Anne and Mary, easily the drunkest of the lot, charged to their weapons and went after the English navymen, hurling invective at the British and the pirates alike. The ladies were vastly outnumbered, but still managed to drive the British back, and it took a massive counterattack to subdue Anne, Mary and their sniveling companions. The crew was clapped in irons and the ship towed back to port.

It was there that authorities discovered they had two women on their hands. This sent the ordinarily speedy and harsh English system of justice into paroxysms of confusion. The English were generally opposed to hanging women, but they always hanged pirates, so what to do? They wanted to believe that the ladies had been forced into piracy in order to save their virtue, but that line screeched to a halt when both Anne and Mary announced they were pregnant and Calico Jack was the father. This disclosure upped the legal confusion ten-fold. The ladies were kept in a separate cell from the men and some of the more chivalrous guards took pity upon them and snuck them extra food and bottles of rum. Even in the moldy confines of their tiny cell, Anne and Mary managed to keep the party rolling.

All twenty-two of the male pirates, including Calico Jack, were found guilty of piracy and hanged. On the morning of the execution the men were lead to the gallows on a route which took them past the windows of the cell shared by Anne and Mary. Calico Jack begged Anne to use her feminine wiles to get him pardoned from the noose, but Anne held her tongue. When asked later how she felt about Jack’s death, she stated she “was sorry to see him there, but if he had fought like a man, he need not have been hanged like a dog.”

Nothing is known about Anne Bonny or Mary Read after this point, as all pertinent court documents were destroyed in a fire. But we can hope they somehow got free and took once again to the seas, drinking, fighting, and pillaging to their hearts’ content. And perhaps in skirts this time, freed from the need for pretense.

She Was a Hellion

The American West of the mid- to late-1800s is chock full of beloved and colorful characters, people who performed the deeds which led to the myths that became this country’s popular history. Their names are familiar to us all, leaping off the page and into our imaginations: Daniel Boone, Batt Masterson, Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, Jesse James, Wild Bill Hickok, Kitt Carson, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday and Buffalo Bill Cody. Missing from the list are the ladies, one of which I’d like to introduce you to:

The American West of the mid- to late-1800s is chock full of beloved and colorful characters, people who performed the deeds which led to the myths that became this country’s popular history. Their names are familiar to us all, leaping off the page and into our imaginations: Daniel Boone, Batt Masterson, Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, Jesse James, Wild Bill Hickok, Kitt Carson, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday and Buffalo Bill Cody. Missing from the list are the ladies, one of which I’d like to introduce you to:

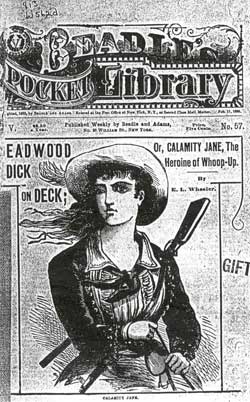

She was an Indian guide, a tracker, and a gambler. She was the subject of dozens of dime novels during her life, and several movies and TV shows in later decades. She could shoot the eye from a rabbit at thirty paces and drink the toughest cowboy under the table and into his boots. Her name was Martha Canary, but we know her better as Calamity Jane.

Calamity was born in Missouri in 1856. Her parents moved frequently while her father looked to make his fortune working restlessly at a variety of trades. Her parents died when she was twelve, leaving Calamity and her two younger sisters orphaned in the wilds of Wyoming near Fort Bridger. History loses track of her at this point (and of her sisters entirely), but she resurfaces in 1875 — newly named “Calamity Jane” by a roving reporter who met her in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory. She was working as the company scout for a gold expedition mounted by Walter Jenny and supported by the US cavalry. She dressed in buckskins and smoked cigars, but everyone was well aware she was a woman. She was such a woman that even the hardened Calvary troops were terrified of her.

Drinking from morning to night, Calamity lead the company into the Black Hills, Sioux country, roaming ahead of the men, locating water, river fordage and campsites. It wasn’t long however, before the men grew tired, and perhaps a bit jealous of Calamity and her wild ways. She was harder to handle than a bucket of rattlesnakes and could generally out-fight, out-shoot, and out-drink any man in the company. Intimidated, they suddenly feigned surprise upon “discovering” that Calamity was a woman. They evicted her from their ranks, forcing her to make her own way back to Wyoming.

Back in Cheyenne, and looking for work, Calamity was a frequent guest at many of the town’s three-dozen saloons. So great was her ability to drink “bug juice” (as the locals called whiskey) that many bartenders cringed upon seeing her walk through the door, while others preferred to cut their losses by banning the woman from their premises altogether. The problem wasn’t necessarily with how much she drank, but about her actions after she got a skinful.

Calamity was a large woman, not fat by any means, but big, and she feared nothing when she got in her cups. Her language was, as noted by the reporter who named her, “not of the Queen’s pure,” and her penchant for expelling great gobbets of tobacco juice in random directions made her a sometimes difficult companion, or at least a hazard to one’s trousers and boots. If she felt cheated at cards her reaction could be extreme, guaranteeing at least fisticuffs and, more often, gunfire.

The citizens of Cheyenne eventually had enough and tossed Calamity in the hoosegow on a trumped-up charge of theft. A local woman charged Calamity with stealing clothing off her clothesline, which is patently absurd — Calamity never cared for women’s’ clothing, and seldom bothered even washing what clothing she owned. It was a transparent attempt to get rid of Calamity, and the righteous judge must have sensed this because he let her off after a five minute trial. He did, however, warn her about engaging in further acts of violence or public intoxication. Calamity spoke meekly to the man—selling her innocence to the hilt—and upon being freed, walked calmly from the courtroom, let out a full-throated whoop, bought a bottle of bug juice, stole a wagon and horses, and whipped them of town, vanishing in a cloud of prairie dust.

Fortune then smiled on Calamity. She traveled back into the Dakota Territory, landing in a small gold-boom town called Deadwood, where she met up with another American legend, the full-time gambler and part-time lawman Wild Bill Hickok. Calamity took to Wild Bill at once. As far as she was concerned, it was love at first sight, and even though Hickok never reciprocated romantically, he allowed Calamity into his circle. Calamity doted on Hickok, and also protected him. No one came near Wild Bill when Calamity was around. One man made the mistake of referring to Calamity as Wild Bill’s “guard dog” and paid the price with a cracked skull.

Wild Bill Hickok was shot in the back while playing cards (holding what’s come to be called the “Dead Man’s Hand” — aces over eights) in 1876 by Jack McCall. Calamity felt responsible for Wild Bill’s death, and departed Deadwood in a dark mood. She decided to go back East for a spell. She took a train to New York where she was surprised to learn she was a major celebrity. Numerous writers had popularized Calamity as a two-gun heroine of the Wild West. Most of the tales were taller than Yao Ming, but they served to make Calamity some much needed cash, and garnered her an invitation to star in the latest form of big-city entertainment: the Wild West Show.

Popularized by Buffalo Bill Cody, a typical Wild West extravaganza featured displays of target shooting, bear taming, trick riding, knife throwing and other activities thought to be commonplace in the western territories. City people went nuts for this stuff, and Calamity Jane was the star of the show. She shot targets with a rifle from the back of a trotting horse, then repeated the spectacle with throwing knives.

Calamity enjoyed regaling packed audiences with her skills, but there were some aspects of her new career that got under her skin. Part of being a New York celebrity in those days meant making public appearances and accepting invitations to the homes of wealthy citizens for tea and other such silliness, all of which required Calamity to wear a dress far more often than she liked. She had to go without her cigars, was unable to spit where she chose, and didn’t particularly care for the way high falutin’ women stared at her in shock when she drank, which was most of the time. She caused uproars by walking into high-end restaurants, staggering drunk and strapped with six-shooters.

By 1900 she’d finally had her fill. She gave up performing and headed back to the relatively more tolerant West.

Calamity Jane died in South Dakota in 1903. She was buried, per the only stipulation in her will, in Deadwood, side by side with Wild Bill Hickok.

A True American Outlaw

The last lady in our survey is another legendary figure of the American West. She was a madam, a horse rustler, a saloon keeper, and well versed in the art of knife-fighting. Her’s was a life lived on the fringes of civilization; the territory occupied by outlaws and outcasts. She crossed paths with the James-Younger gang, lead by the James Boys, Frank and Jesse, and formed a special relationship with Cole Younger. She was born Myra Maybelle Shirley in 1848, near Modoc, Missouri, but is remembered by her married name, Belle Starr.

Even as a girl, Belle preferred the outdoors and trousers to kitchens and skirts. When the Civil War exploded across the land, Belle left home and earned money by spying on the Yankees. She also traded in liquor, stealing from the North and giving to the South, a sort of Rebel Robin Hood. She relocated to Texas after the war and opened a saloon near Dallas. There she made the acquaintance of Jesse James and Cole Younger. James and Younger were wanted men, and Belle hid them from the law for three weeks (Jesse would stay with Belle again a few years later, just before his death).

She would also meet and marry a Cherokee named Sam Starr. They sold the saloon and took up lives as “free entrepreneurs,” which to them meant playing fast and loose with local laws and customs. Belle took to wearing a Mexican sombrero and carrying a Colt pistol she called “my baby.” Her forbidding appearance was threat enough to get her free drinks in many saloons. Rarely did she pay a bar tab; saloon keepers preferred to comp the woman rather than incur her wrath.

Around this time people began to speak of Belle Starr and Her Gang, though Sam, tough as he was, could hardly count as a “gang.” It seemed impossible that Belle and Sam alone were responsible for the many deeds attributed to them, so they must have had a gang.

Eventually the gang of two was caught and convicted for rustling horses. Belle served her time in Texas; Sam was shipped to a Michigan prison.

Reunited after their release, the pair attempted a normal life, but it wasn’t long before Sam got mixed up with several robberies. Though Belle wasn’t involved, the press named her the leader of yet another fictitious “gang.” Sick of being constantly hassled by the Man, Belle confronted the circuit judge, and managed to get all charges dropped against her and Sam both. Word failed to reach an over-zealous deputy sheriff, however, who shot Sam in the back, killing him.

Belle lived alone for a while before taking up with another Cherokee, Bill July, and moving to Fort Smith, Arkansas. They engaged in facets of the liquor trade, acting as “middlemen” for shipments of Southern whiskey travelling west by wagon train. This meant they would steal the whiskey, find a buyer, jack up the price, and make a killing. If they swiped a particularly tasty batch, they would only sell a portion and enjoy the rest themselves. Belle was known as something of a connoisseur in regards to whiskey. Refusing the usual rot-gut purveyed at many local establishments, she would use her reputation to bully bartenders into giving her bottles of the good stuff.

Though Belle had been out of the horse-thievery business for years, accusations continued to fly her direction. Then, one fateful day in February, 1889, she rode into Fort Smith to let the local constabulary know exactly how she felt about a recent accusation. As she rode back out of town, some unknown person shot her in the head, killing her instantly. She was buried in Fort Smith, her revolver in her hands and a bottle of whiskey in the coffin.

In later years, Belle Starr’s life would achieve a mythical status. Writers called her the “Queen of the Bandits,” despite the fact that she’d never really done any real banditry, per se. Nothing they could prove, anyway. It would have been more apt to call her “Queen of the Whiskey Raiders.” Except they never proved that either.

(Note: The author is indebted to the works of Joan Druett, David Cordingly, Glenda Riley, Richard W. Etulain, Charles Ellms, Peter Beresford Ellis, and H.R. Ellis Davidson)