In 1950 Jackie Gleason was going everywhere and nowhere at once.

He was getting plenty of work on Broadway and in the nightclubs, even a few TV and radio gigs, but nothing steady. Certainly nothing resembling that gleaming rocket ship he’d long thought was going to materialize in front of his apartment one fine morning, fueled up and ready to blast him to super-stardom. He’d been waiting for that ride for eight long years—since he’d been rejected by Hollywood—and he was starting to wonder if he’d made a miscalculation somewhere along the way. A strange melancholy began creeping into his stand-up acts, made all the more noticeable because Jackie relied heavily on ad-libbing. Whatever emotions he brought to the stage was what the audience got. And at the moment he was bringing a lot of grief and anger.

Waiting for the Rocket Ship

Not to say Jackie was spending his off time sitting at home, wistfully staring at the telephone, waiting for opportunity to dial his number. He much preferred to wait out his fate in places that served strong drink, notably Toots Shor’s Nightclub in Manhattan. The bar’s namesake and proprietor was a stocky Jewish pug who’d toiled his way up from busboy to bouncer to owner of NY’s most celebrated nightspot. Jackie, the brash, eternally up-and-coming drunkard comedian, and Toots, the rags-to-riches hard-drinking bar owner, took to each other at first meeting. “If a bum ain’t drunk by midnight, he ain’t trying,” Toots was fond of saying, and Jackie wasn’t the sort to let his friends down. In Jackie, Toots found an ever-ready drinking pal, always quick with the charm and a joke. In Toots, Jackie found a foil for his bawdy wit and, perhaps more importantly, an endless bar tab. Toots may have been a tough, street-wise bastard, but at heart he was a soft touch, the perfect companion for Jackie’s perpetual thirst for hard liquor and good times.

Most people, when they’re heavily in debt to their friends and have to borrow money almost every day, tend to become a tad frugal, they tend to lay off until the horizon gets brighter. Not Jackie. Dead broke, he would borrow a hundred dollars from Toots just so he could rent a limousine to drive himself and Frank Sinatra to a nightclub a block away, where he would borrow another hundred to bribe the band leader into playing the same song over and over again, just to drive the audience crazy.

“At one time he was into me for over $10,000,” Toots recalled. “I gotta hand it to him though, when he got into the big money, he came by and handed me the cash, saying, “Here’s what I’m sure I owe you.”

That amount is all the more impressive when you realize it bought about twenty thousand drinks in those days. Jackie would later claim sound psychological reasons for running up such outlandish tabs. “They were expressing a confidence in me,” he said, “that I didn’t have myself.”

Jackie eventually learned to bypass the tab entirely by frequently challenging Toots to drinking contests. The prideful Toots, who would bristle under his Irish friend’s claims that Jews couldn’t hold their liquor, almost always accepted the challenge and the battle of booze titans would begin, drawing star-studded audiences. Jackie didn’t always win and it didn’t really matter—since Toots was one of the combatants, it was expected the bar would pick up  the tab. When Jackie won, he ordered victory drinks on the cuff and Toots was in no condition to protest. When he lost, he’d oftentimes slide off his bar stool and pass out on the floor, where Toots would let him remain as a testimony to Jewish drinking prowess. Tourists were sometimes scandalized, but the regulars became used to stepping over a supine Gleason.

the tab. When Jackie won, he ordered victory drinks on the cuff and Toots was in no condition to protest. When he lost, he’d oftentimes slide off his bar stool and pass out on the floor, where Toots would let him remain as a testimony to Jewish drinking prowess. Tourists were sometimes scandalized, but the regulars became used to stepping over a supine Gleason.

The pranks they played on each other became grist for the gossip columns. Sometimes they were light-hearted, sometimes they bordered on outright cruelty. Jackie, for instance, knew Toots had a terrible phobia about elevators. So whenever Toots went to visit his lawyer’s tenth-story office, Jackie would manage to be there, cutting the elevator’s power from the lobby, leaving his pal stranded in the dark between floors. Gleason reveled in recalling that pedestrians could hear Toots’ blood-curdling screams for blocks.

Toots wasn’t always an easy target. Once when Jackie popped in for his morning eye-opener, he found Toots sobbing uncontrollably over the death of long-time friends.

“They’re all gone, Jackie,” Toot’s cried, blinded by tears, “they’re all gone!

“Yeah, I know, Toots.”

Noting his pal’s condition, Gleason went around the club, picking up every unpaid bar tab, then sat back down next to his friend. Jackie pushed a tab in front of him and said, “Here, Toots, sign this.”

Toots, without looking, signed the tab. Jackie kept sliding him tabs and Toots signed them all.

The next morning a gleeful Gleason returned, eager to see how his prank went over. He hadn’t finished his first double scotch when the Maitre d’ came over and handed him the stack of tabs saying, “I believe these are yours, Mr. Gleason.”

Toots had signed Gleason’s name to every one of them.

Other celebrities enlisted in the war of wits. One evening, when Jackie was deep in the scotch and especially braggadocios about his pool playing skills, Frank Sinatra offered to pit Jackie against his tailor for the night’s tab of drinks. Jackie quickly agreed and Frank called in a slight man who indeed looked the part of a tailor. Jackie grandly offered to let the stranger break. The man proceeded to run the next six tables. The tailor was in fact Sinatra’s recent acquaintance, pool champion Willie Moscone. Jackie put the night’s drinks on his Teflon tab.

Jackie didn’t always fall short of his boasts. He and fellow heavyweight drunkard Orson Welles were boozing up a storm at the Stork Club when Welles broached the subject of Shakespeare. Jackie claimed to know much of the bard’s work by heart, and Welles, doubting this Brooklyn grade-school dropout’s boast, intentionally misquoted an obscure line from Aeschylus. Jackie Gleason immediately corrected him, prompting Welles to declare, “You’re the Great One!” The name stuck.

Jackie would again display his prodigious knowledge of Shakespeare’s work during a drunken argument with theatre critic Brooks Atkinson at Toots Shor’s. Atkinson, playing down Gleason’s Broadway performances, declared that no actor was worth a damn until he could do Hamlet. Jackie pushed his way to the center of the bar and, thoroughly smashed on scotch, delivered the entire soliloquy from Hamlet without fumbling a single word. Witnesses swore Barrymore couldn’t have done it better.

The Gang’s All Here

Picture it: It’s 1950 and you stroll into Toots. The first thing you take in is the circular bar, lushly appointed and wrapped around a spire of liquor stacked to a distant ceiling. In the deepest corner of the room a crowd roars with laughter and you naturally gravitate toward the source. First you pass through a sea of gawking tourists willing to pay premium drink prices to get a glimpse of their idols, then a moat of newspaper columnists, their ears cocked for material for tomorrow’s column, then finally the inner circle itself—Frank Sinatra drinks Jack Daniels with known mafia kingpins, Humphrey Bogart nurses a double whiskey and a triple hangover, Joe DiMaggio pours champagne for his wife Marilyn Monroe. Milton Berle, Charlie Chaplin, Bob Hope, Walter Winchell and Mickey Mantle stand enthralled, waiting for the next hilarious word. At the very center of this thick ring of American heroes stands the then relatively unknown Jackie Gleason, holding court, doing what he does best—working the room for laughs. He makes light of himself, he makes greater light of those around him; mining huge egos for uproarious laughter. And they take it, daring not to show weakness, because if Jackie smells blood he goes in like a shark.

This was before he became television’s biggest star, but those in the audience knew something big was going to happen to this cat.

And it happened on a lark. With his industry-wide reputation for boozing before, during and after work, it should have been difficult for Jackie to get a good job. But it wasn’t. Jackie was the ultimate super-functional alcoholic; he was almost always on time and always knew his lines, and what lines he got he polished into comedic nuggets. The actors he worked with thought him a scene-stealer, but writers loved him. He could take the most innocuous joke, and with sheer, over-the-top body language, twist it into a show-stopping riot of laughter. So it was with little trepidation that a variety show called the Cavalcade of Stars hired Jackie for a two week gig as emcee.

A Brash Leap to Stardom

A Brash Leap to Stardom

The Cavalcade of Stars certainly didn’t appear a springboard to overnight success. Broadcast by the DuMont Network, which eked out a subsistent existence in the shadow of the big three networks, the show was languishing in the ratings and was going through hosts faster than Jackie went through Toots’ good scotch. The producers decided they needed a raw, over-the-top talent to grab the TV viewers’ imaginations, so, after catching one of Jackie’s raucous booze-fueled spectacles at Club 18, they gave him a shot.

Jackie didn’t walk in as a timid tourist to live TV—he had already been through too much—he stormed in like Atilla the Hun. Remembering his maddening tenure as a powerless cog in the Hollywood machine, Jackie insisted on, and got, full control of the production.

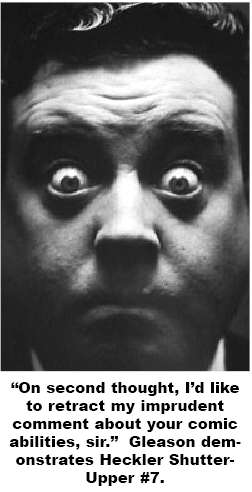

Like many men who have been proclaimed geniuses, Jackie was a bit of a control freak. Early television was a very limited visual medium. In this era of digital big screen television it’s difficult to appreciate how small and fuzzy the signal was back then. Televisions were tiny grey windows families peered into and hoped to make out what the hell was going on. Jackie knew what he was dealing with and discarded nuance and subtlety for in-your-face glitz and broad physical gags. He understood that if you wanted to get someone’s attention from behind a tiny and shrouded window, you had to wave your arms and shout for all you were worth. He hired dancing girls to precede his arrival on stage, he invented camera angles and movements that were nothing less than heresy back then. Most important of all, he delivered larger-than-life performances Americans had no problem noticing, no matter how small and grey the window.

Through the Glass, Snidely

Through the Glass, Snidely

It was during that first season that Jackie formed the stock characters he would use throughout his career: the hapless Poor Soul, the bumbling Bachelor, the long-suffering Joe the Bartender, and Jackie’s personal favorite, Reginald Van Gleason III.

Reginald was the guy Jackie always secretly dreamed of being. An irresponsible, womanizing playboy scion of an old money family, Reggie’s only concern was finding a home for all the orphan bottles of booze in the world. That home being, of course, his tuxedo-clad belly. A snobbish rogue ever quick with the insult (and ever reaching for a drink), this carnival-mirror reflection of the barroom Jackie delivered some of the funniest lines of early TV. A distant gong would echo every time Reggie took a sip of booze and he’d deliver the trademark line that would soon echo in bars from coast to coast: “Mmmmbooy, that’s good booze!” Of course, if that gong had followed Jackie into Toots’ joint after work, it would have sounded like a fire-alarm.

In one memorable skit Reggie is hauled bedraggled drunk before a judge. The judge demands to know what he was up to last night and Reggie dryly replies, “Coming home from a New Years Eve party.” A seemingly reasonable response until the judge informs him it’s the middle of July.

Reggie became so famous a character that legendary newsman Edward Murrow arranged to interview him. Taking in the sprawling miniature train set surrounding the playboy, Murrow inquired: “Are model trains your hobby, Reggie?” A locomotive chugs by with a shot of whiskey, Reggie whisks it to his mouth, replies, “No, booze,” then downs it in a single gulp.

It was in the first Reginald Van Gleason III sketch that the television world was introduced to the man who was to become Gleason’s greatest comedic foil: Art Carney. Carney played an effete photographer shooting the playboy for a scotch company’s print ad. Reggie, for the sake of veracity, lays into the product and by the end of the skit they’re both loaded and Reggie’s photographing the hilariously drunk Carney.

Instantly recognizing their natural chemistry, Jackie signed Carney up and they set about creating the characters that would earn them everlasting fame: Ralph Cramden and Ed Norton.

The Honeymooners, which started out as a short sketch, was a gift of Gleason’s dark memories of his childhood. All the other competing shows on television featured comfortable middle-class settings and Jackie was determined to appeal to the ignored working-class Everyman. Ralph Cramden, he determined, would subsist on a low-paying job and languish, forever scheming for a better life, in a bare Brooklyn tenement with no curtains and no pictures on the walls, an accurate reflection of the bleak apartment he grew up in. That’s where the verity ended however, he insisted that every skit end with the embattled Ralph and Alice in a happy clinch, kissing after delivering his trademark line, “Baby, you’re the greatest.” It was the happy ending Gleason craved as a child but never caught sight of.

The switchboards lit up when the skit aired and they knew they’d hit a nerve. The Cavalcade of Stars became DuMont’s greatest success. The two-week contract doubled into a four-week run, then two full seasons.

Jackie brought in an old drinking pal from Hollywood, Harry Crane, the writer of the superlative, super-lubricated Thin Man films. Harry knew his old buddy was a boozer without equal but was not prepared for the hooch hurricane he was about to walk into.

“I went up to Jackie’s apartment this first day and it sounded like (Count) Basie live,” Harry recounted. “Dixieland bands were playing. Broads were all over the place smooching guys. It was like Sodom and Gomorrah in prime time.

“I walk into this cold, and say, ‘Jackie, we gotta talk about this script. There are sets to be built.’ He says, ‘Grab a broad and some booze and we’ll talk Thursday.’ Now, Thursday is 24 hours before airtime. Nothing to do but come back Thursday. This time the apartment looked like a suicide pact. Bodies passed out, strewn all over the apartment. I leave, and as I walk though the lobby, mothers grab me. ‘My daughter’s up there! Is she still alive?’

“Later that same day, I go back up. Snap! Crackle! Pop! The party’s on again. Everybody is dancing. Max Kaminsky’s band is playing. Gleason is dancing steps that haven’t been invented yet. No chance to talk script, so I left again.”

Desperate, Harry hunkered down and cranked out three scripts, all based on stock Gleason characters. A few hours before airtime Jackie glanced at the pages for a few moments and quipped, “Gotcha, pal.” Much to Harry’s dismay:

“Gotcha, pal? What the hell kind of show have I got myself into? I go back to the set. All the other actors are in a panic. They don’t know what the hell they’re going to do. No rehearsals. No chance to study the script. No nothing. Finally, Jackie shows up about an hour before airtime. The other actors are all over him, screaming, ‘What the hell do we do? What the hell do we say?’

“Jackie has a stock answer for everyone: ‘Every man for himself.’ Every man for himself? On a live show that’s going on the air in minutes to twenty million people? I ducked out. I didn’t have the stomach or heart to watch a catastrophe. I went to the bar next door. I ordered doubles. Set ‘em up in the next alley. The bar television was tuned to the Gleason Show. I couldn’t believe what I saw. Gleason, who had just glanced at my script, was doing every line perfect. He didn’t miss or flub a word. He was hilarious. Everybody in the bar was laughing their heads off. What had been absolute chaos only an hour ago was comedy at its finest. I had to be working with a genius.”

Sometimes there was no script at all. On one occasion he threw the writers’ efforts into the trash bin and sat down with his co-stars and a typewriter to work something up on their own. They started pouring drinks and two hours later, with minutes before they were to go on live TV, they had the title and nothing else but a good buzz. So they ad-libbed. And it turned out to be the funniest show of the first season.

Jackie was making a cool grand a week and ten times that much when he made guest appearances on other shows. One show he refused to get paid for was a variety hour hosted by his old drinking buddy Frank Sinatra. Touched by his kindness, Frank walked Jackie to the studio parking lot after a show and presented him with the biggest Cadillac limo he could find, complete with the gold leaf emblem: “From F.S. to J.G. with love.”

Behind the wheel and under a chauffeur’s cap sat Toots himself, ready to shuttle them from bar to bar. They jumped in and the already drunk Toots nearly ran over a pedestrian who, recognizing the passengers, shook his fist and yelled, “You rich cocksuckers!”

“For some strange reason,” Jackie recalled, “that upset me. I never rode in or drove that car after that. I don’t know what the hell happened to it.”

Regardless of the fate of the limo, volunteering for Sinatra’s show turned out to be one of the smartest moves Jackie ever made. His hilarious performances caught the attention of CBS President Bill Paley, who immediately recognized Jackie’s rich talent and told his second-in-command three words: “Get me Gleason.”

Multi-Million Dollar Baby

CBS was the most powerful and wealthiest of the networks and Gleason negotiated the largest salary known to television up to then—eleven million dollars for two seasons. Instrumental in landing such a sweet deal was Jackie’s apparent nonchalance: the night prior to the final negotiating session, Jackie went on the town with artist Salvador Dali and singer Johnny Ray.

“Jackie Gleason was an artist who was fueled by liquor and his childhood memories,” Dali would later say. “Like Cinderella, when I was out with him, I always tried to be home by midnight, because I couldn’t keep up with his nonstop pace. The man had phenomenal energy.”

This particular night Jackie wouldn’t let Dali scuttle off when the clock struck twelve. When a thoroughly wiped-out Jackie arrived at the negotiation luncheon, he promptly demanded a beer, drank it, then fell asleep at the table. Which turned out to be a very clever, if unintentional, strategy. Intrigued, Paley stared at the snoozing Gleason and said, “He can fall asleep while we’re discussing whether he gets nine or eleven million. If that’s really his attitude, give him what he wants.”

Jackie wanted it and he got it in spades. The first thing he did after waking up was demand a $75,000 advance, which he promptly spent leasing and transforming a penthouse atop the luxurious Park Sheraton Hotel into the headquarters of his entertainment empire. It resembled a sultan’s palace more than a place of business, and he made sure it was outfitted with a pool table, dance studio and four bars, staffed by a live-in bartender. Over the massive fireplace Jackie hung a picture of the character whose lifestyle Jackie had long envied and had now had firmly in his grasp: Reginald Van Gleason III. On a gold plaque beneath the portrait it read, Our Founder.

Another perk of the deal was CBS agreed to build a house to Gleason’s specifications in upstate N.Y. And what a house. He called it the Mother Ship because he designed it to resemble a flying saucer (Jackie had a lifelong fascination with UFOs). It came complete with a dance hall, recording studio, pool hall, and twelve fully-stocked bars. For Jackie it was a dream come true—walk 20 steps in any direction and you were stepping up to the bar. How sweet it was.

With some time off before his first season as CBS’s golden boy, Jackie camped out at Toots Shor’s with Sinatra and his celebrity pals. One evening Frank showed up during Jackie’s morning eye-opener with four tickets to the sold-out final playoff game between the NY Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers. J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, was having a tête-à-tête with Toots and Frank invited the trio to accompany him to the game. Everyone agreed except Jackie, who wanted to stay at the bar and drink. They finally talked him into it by renting a fully stocked limo. Sinatra recalls:

“We pile into that limousine, already feeling no pain, especially Gleason. Jackie guzzled booze all the way to the Polo Grounds and ate most of the food. When we get there Jackie switches to hot dogs and beer. Comes the last half of the ninth and the fans are going wild. The Giants are behind 4-2 and Bobby Thompson comes to bat.

“Right at the exact moment, with the crowd screaming, Gleason throws up right on me. Here is one of the all-time classic games that people will talk about and I am right in the stadium and I don’t see Bobby Thompson hit that home run. Only Gleason, a Brooklyn fan, would get sick at a time like that. But that’s not the punch line.

“On the drive back to Toots, Gleason keeps muttering to the chauffeur to pull over to the side of the road saying, “Let’s throw this bum Sinatra out of here. He’s smelling up the limo.”

Some nights Jackie would show up at the bar with a baseball bat and glove, get loaded, then go hit fly balls to Joe DiMaggio in Central Park in the middle of the night. He also liked to stage fake fistfights with rookie sensation Mickey Mantle, just to mess with Toots’ head. Other times he’d bar hop with Humphrey Bogart, who would try his best to get Gleason into fistfights with whoever happened to be the biggest guy in he bar.

“There’s no pleasure in being just a spoke in a wheel, I’d rather be the whole wheel,” Jackie was fond of saying, and if he’d been a control freak at DuMont, he really cranked up his act at CBS. He demanded and got oversight of the smallest minutiae, from what shoes the dancers wore to the brand of microphone he would speak into. He brought in more dancers, he hired a slew of ‘Glee Girls’ whose only job was to look gorgeous, light his cigarettes and bring him his infamous teacup.

A teacup only in word, because now Jackie, fully in charge, insisted he would not only drink on the set, he would drink while in front of the camera.

It’s hard to appreciate the sheer audacity of this decision until you examine the character of early television. Because the signal was beamed directly into the sacred American home, where grandma and the kids lived, networks sanitized their programming to the point of self-satire. And the networks expected the stars of the shows to be squeaky clean off-camera too, which was, of course, impossible for Jackie. This was the age of the all-knowing, all-powerful gossip columnists and many of them drank in the same bars Jackie did. His drunken antics soon graced the pages of newspapers from coast to coast, much to the ever-mounting horror of CBS. They knew beforehand he was a little hard on the hooch, which is akin to saying Stalin was a little hard on the Ukrainians, but they figured all the millions they shoveled at him would convince him to put a clamp on it. Or at least be a little more discrete.

And there this beautiful son of a bitch was, drinking scotch from a teacup for all of uptight America to see, daring someone to try to stop him. And he didn’t disguise his defiance, after every slug he’d grimace a little, wink at the camera and say, “Mmmmboy, that’s some good coffee!” (Though he drank from a dainty teacup, he always called it coffee, but what the hell difference did it make, since it was neither.) He also made a point of casually mentioning certain brands of liquor during the skits, knowing the distilleries would send him a case of their product for doing so. One can discern he was a man of good taste, because he only mentioned top shelf vodkas and scotches.

To the additional chagrin of the network, he refused to rehearse. The very idea was loathsome to him. Not only did rehearsing cut into his drinking time, he felt it was detrimental to the creative process. The way he figured it, why practice something until it was stale when you could just wing it and turn in a fresher performance? His idea of rehearsal was reading the script once (much like that other great drunk, Humphrey Bogart, Jackie possessed a near photographic memory), then have a stand-in run through the skits with the other actors while he watched from a TV monitor, drinking scotch.

He understood that as long as he didn’t muck it up on camera, the networks couldn’t do much. And he never mucked it. Not much. Even when he forgot his lines, he possessed the skill to ad-lib lines that were at least the equal of the script’s. He was also savvy enough to surround himself with actors who were fast enough on their feet to adapt to the skits’ wild new directions, although sometimes Audrey Meadows would go home and cry afterwards.

Keeping pace with his empire’s expansion, Jackie took on a large well-paid entourage, at one point employing 50 people to attend to his personal and business needs, whether it meant mixing him a drink or running down to the liquor store for more vodka. Some of his cronies had titles and specific duties, but most merely existed solely to keep him company during his benders. And why not? Just because they lacked his talent didn’t mean they didn’t deserve to drink until dawn seven nights a week. The golden grail from which he drank was runnething over, and he was more than happy to let it spill into the mouths and pockets of his pals.

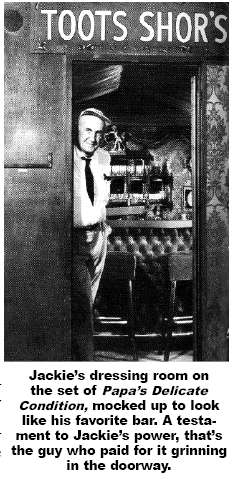

And flowed it did. His biggest, wholly uncontrollable expense was the never-ending party, which started in his dressing room, moved to Toots’ place, then finished up at his Manhattan penthouse or the Mother Ship, with the now flush Jackie picking up the tab (instead of hitting up Toots for a hundred bucks when he came up short, he’d now hit up the studio for fifteen grand.)

His long-suffering, devoutly Catholic wife Gen would read about the parties in the gossip columns and tremble with rage. Not because she wasn’t getting her share — Jackie was very extravagant with the family he never saw — but because he seemed to be having so much fun without her. In fact, she was never invited. But why would she be? She didn’t like to drink, never laughed at his jokes, insulted his drunk friends and always wanted to go home at midnight. Jackie didn’t even hit stride until his twentieth drink was going down and the sun was coming up.

How to Drink Your Way to Success

Jackie was fully in the center of thebooze tunnel now—if before he’d been a prodigious drunk, he was now Bacchus incarnate, possessing not a shred of remorse or restraint. If you’re a drunk, and I suspect you are, you’re in a unique position to understand Jackie’s motivations—to him, life was not a brute struggle of survival and endurance; it was a contest to see who could squeeze the most excess and joy from every passing moment, to spin into gold each waning day. Jackie was 40 years old now and he had no interest whatsoever in living moderately so he could later solemnly tack grey moments onto the tail end of a long monotonous march to the grave.

Jackie was fully in the center of thebooze tunnel now—if before he’d been a prodigious drunk, he was now Bacchus incarnate, possessing not a shred of remorse or restraint. If you’re a drunk, and I suspect you are, you’re in a unique position to understand Jackie’s motivations—to him, life was not a brute struggle of survival and endurance; it was a contest to see who could squeeze the most excess and joy from every passing moment, to spin into gold each waning day. Jackie was 40 years old now and he had no interest whatsoever in living moderately so he could later solemnly tack grey moments onto the tail end of a long monotonous march to the grave.

When even his boozy friends started chiding him about his insatiable appetite for drink, food and smoke (he smoked five packs a day until the day he died) his stock answer was, “I want to live, baby!”

In the backdrop of these grand times, The Jackie Gleason Show dominated the airwaves. Not that Jackie paid too much attention. He didn’t even own a television set. “I never bought a set because I was never at home to watch it,” he recalled. “I thought television was something that distracted from my drinking. It interfered with the good fellowship of conversation at the bar.”

He expanded The Honeymooners skit into a full half-hour sitcom, then turned over the second half hour to his long time drinking buddies and legendary band leaders, the Dorsey Brothers. This left time for Jackie’s sundry other interests; he was always flying off in some new direction, whether it be opera, serious acting, music or nightclub design. He’d throw money at some new project, then get distracted and move on to something else. Most of his schemes didn’t pan out, but one that did ended up making him millions.

While wooing one of the Glee Girls, he decided he’d compose several original ballads to serve as the love letters he didn’t have the patience to write. Spending tens of thousands of dollars on the orchestra, he recorded two songs that sounded so good he decided to record an entire album. Jackie had a vision of creating a massive catalogue of lush, romantic mood music geared to the masses. He couldn’t play an instrument, so he hummed his melodies to a song writer, then supervised the production.

Problem was, no music label was willing to back him. His friends snickered behind his back—it was just another of Gleason’s wild-ass, dead-end schemes, they figured. What did a television comedian know about orchestra music? And that type of music didn’t appeal to a large audience, anyway, the kids wanted rhythm and blues and they were the ones buying all the records.

But Jackie sensed the Average Joe had a hidden romantic soul and he set out to capture it. He personally funded the record’s production, then talked Capitol Records into releasing the album, For Lovers Only.

It went on to sell half a million records. Before he was through he would put out twenty more records and sell tens of millions of copies. Every album was imbued with a lush sentimental romance and invariably linked to drinking. They featured melancholy titles like Music, Martinis and Memories and Music To Make You Misty and covers with forlorn and beautiful women drowning their sorrows with various forms of liquor and wine.

One notable two record set called Lover’s Portfolio comes with a guide book describing what cocktails you and your amour should drink while listening to each side of the records. The first side is called Music for Sippin’, the last (rather optimistically) is titled Music For Lovin’. Nineteen different drinks are recommended, recipes included, and if the two of you weren’t lovin’ by the final song it was most likely because you were both passed out.

Jackie re-upped with CBS in 1955 for fourteen million more dollars, with Buick coming on board as the sugar daddy sponsor. This was that golden year that Jackie decided to film rather than tape The Honeymooners, preserving what is known to fans today as The 39 Episodes or The Perfect Season. These are the classics that are perpetually played in syndication.

“How sweet it is!” was the bellow Jackie used to open every show and he meant every syllable. Performers tend to be terrific liars, masters of putting up facades that have nothing to do with their personal lives, but Jackie meant what he said. As soon as the show was finished he’d be found in his dressing room with a towel around his neck, sweating like a prize-fighter who’d just went the full fifteen rounds. Not that he was ready to call it a night. The way he figured it, he’d done his nasty job and had earned a full-bore night on the town. He’d have a couple double scotches from the dressing room’s minibar, shower, change into a natty suit, then bolt for Toots’ for his just desserts.

Jackie finished The Perfect Season without a hitch, then promptly announced he wouldn’t stick around for the second season, which meant he’d lose the remaining half of the Buick contract, which added up to seven million bucks. He dropped that bankroll as nonchalantly as he’d drop a hundred bucks on a bartender at Toots’.

You have to understand that Jackie knew the password at this point, he was the highest paid performer on TV, the studio execs were thoroughly terrified of him and eager to bow to his every demand, however insane and whimsical. He could have rode that cheap pony until the day he died but instead—he told them to fuck off.

Jumping Off the Carousel

Why? What would make a man who had the world at his feet give it a solid kick and send it rolling away?

He merely shrugged to the media, telling them he’d pushed The Honeymooners as a concept as far as it would go, that he loved the show too much to sully its memory with bad scripts and half-hearted performances.

The real reason, he would later reveal, was this: he was terminally bored. What was the point, he mused, of being comfortably successful? Certainly not the money, he threw that away like it gave him a rash. Creatively the show gave him no pleasure, Ralph Cramden was by necessity an unchanging constant—if one of Ralph’s wild schemes ever did succeed, he would no longer be Ralph Cramden.

To him The Honeymooners had become a merry-go-round, a nice, safe ride, and there was nothing Jackie loathed more than the easy gig. He was suspicious of facile success. He always felt he was at his best when he was struggling to stay afloat in a raging sea of uncertainty; once life’s waters became calm the sharks of his deep-seated insecurities began to circle. Now that he was at the pinnacle of success with nowhere to go but around and around, he took a dive.

Which shouldn’t have been a shock for anyone who knew him well. Throughout his life, Jackie was not only the type to not look before he leapt, he would make a blind running lunge at the cliff with a double scotch in his hand while tossing wisecracks over his shoulder. He’d done it enough to understand he would always manage to land on his feet, he possessed an innate sense of balance that acrobats would kill for.

Having bought back the days of his life, Jackie went on a boozing spree. He told reporters he was busy researching any number of projects, even a novel, but the book must have been about drinking because he appeared to be doing all his research in NY nightclubs.

“I think everyone should make two fortunes, one to blow, to really live it up, and then the other for security,” Jackie liked to say, but he never seemed able to identify the boundary between the end of the former and the start of the latter. By then his music was making him millions and spending that kind of money isn’t the easiest thing in the world to do, though he certainly tried. It’s a pretty safe bet that Gleason spent more money on booze than anyone else in the 20th century. He didn’t drink it all himself, of course, he had legions of helpers. You not only didn’t go thirsty in his company, you were badgered into drinking your personal best and beyond.

By now Gen had finally had enough and gave him is long-sought divorce. Ironically, he would subsequently woo and marry a succession of women who were very similar to her—devout, pristine Catholics lurking in the bodies of leggy dancers. He philandered quite a bit, but probably not as much as his wives suspected and the gossip columnists claimed. When one of his wives investigated a whorehouse he frequented, she discovered he only went because he enjoyed the atmosphere of its bar.

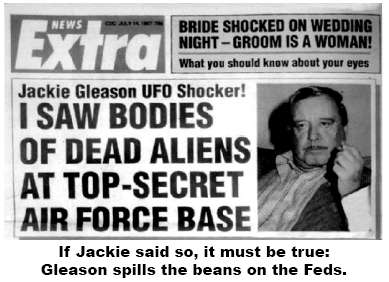

When he found he couldn’t drink all his money, he started spending small fortunes on explorations of occultism and UFOs, two fields that had long fascinated him. His recently acquired insomnia allowed him to devour hundreds of books speculating about strange, unexplained phenomena and aliens plotting amongst humanity. He loved to argue the subjects and during one knock-down drag-out debate with a newspaper columnist at Toots Shor’s, he received an unexpected affirmation of his beliefs. Gleason assured the columnist that UFOs had been seen by both sides during World War II, and that four Presidents had told him they were real. The columnist scoffed until General R. O’Donnell, the head of the Strategic Air Force Command, overheard the two arguing, walked up, whispered, “Jackie’s right,” then walked away.

When he found he couldn’t drink all his money, he started spending small fortunes on explorations of occultism and UFOs, two fields that had long fascinated him. His recently acquired insomnia allowed him to devour hundreds of books speculating about strange, unexplained phenomena and aliens plotting amongst humanity. He loved to argue the subjects and during one knock-down drag-out debate with a newspaper columnist at Toots Shor’s, he received an unexpected affirmation of his beliefs. Gleason assured the columnist that UFOs had been seen by both sides during World War II, and that four Presidents had told him they were real. The columnist scoffed until General R. O’Donnell, the head of the Strategic Air Force Command, overheard the two arguing, walked up, whispered, “Jackie’s right,” then walked away.

Gleason’s second wife, Beverly McKittrick, claimed Jackie was given an even grander affirmation by President Richard Nixon, Jackie’s frequent golfing partner. According to her, Nixon ditched his Secret Service entourage, picked up Jackie and drove him to a heavily guarded compound at the Homestead Air Force Base in Florida. There he showed Jackie the wreckage of a crashed alien spaceship and the frozen bodies of dead extraterrestrials. Beverly claimed the event heavily traumatized Jackie—he couldn’t sleep for weeks and had to double his usual intake of alcohol just to get back to normal.

Not that Jackie needed a glimpse of dead aliens to give him a reason to drink. He had a lifelong habit of drinking heaviest while working and in 1958 he went back to prime-time, repeatedly switching networks and signing ever larger deals. Ever fearful of creeping ennui, he experimented with a variety of formats including a game show (You’re in the Picture, 1961) so bad he went on air to apologize for it; a brilliant one-on-one talk show (The Jackie Gleason Show, 1961) and a satirical comedy program (Jackie Gleason’s American Scene Magazine, 1962-66).

Boozing Against the Dying of the Light

As he got older Jackie developed a fanatical love of golf and decided to move his revived Jackie Gleason Show to Miami Beach. The city provided him with a house right on the golf course and helped finance an additional home built to Jackie’s specifications. This time a more mature Jackie eschewed the bizarreness and inefficiency of the Mother Ship and designed a Hearst-style palace with a single but vast circular bar the size and style of the one in Toots Shor’s. Jackie personally designed the bar stools, which he claimed were impossible to fall out of, no matter how drunk you tried.

“I would have defied any of my old drinking pals like Toots or Bogie to fall of those stools,” Jackie boasted. “Even W.C. Fields would have felt safe in them.”

He continued to insist on complete control of his show, ever the mote in the network’s eye, ever unwilling to bow to their wishes. And because he never bowed, he was never handed one of the riper plums of playing by the rules: an Emmy. Did he want one? Probably. Did he want one enough to cut out the fun and grovel a little bit? Not in a million years.

Jackie was not above using booze as a weapon of sedition. After absorbing a series of veiled insults from his current boss, NBC President James Aubrey, he invited the exec down to Florida for a meeting. Jackie, putting on his kindest face, cajoled Aubrey into drinking with him. He repeatedly got Aubrey roaring drunk then unleashed him on a number of high profile parties where the light drinker made a fool of himself. Gleason made sure NBC’s board of directors got wind of every lurid detail. Aubrey was called to the carpet and fired two weeks later.

Jackie began experimenting with serious roles on stage and TV, bowling the critics over with surprisingly subtle performances. Not surprisingly, he almost always played the role of the irascible drunk and stayed well lubricated at every stage of the production. It was all about staying in character, he insisted.

He made a name in film as well, earning an Oscar nomination with his sublime performance as Minnesota Fats in The Hustler. He drank and played pool with co-star Paul Newman off set, culminating with a $3000 bet on a 50 ball game of pool. Under Willie Moscone’s tutelage, Newman had come to think he could beat the Great One. Jackie let Newman break, then proceeded to run the next fifty balls. Newman paid him in pennies.

Though now aggressively pursued by Hollywood, Jackie agreed to play a rather lowbrow role as the redneck sheriff in Smokey and the Bandit because he knew Burt Reynold’s reputation for insobriety and figured it’d be a good time. Awed by the Great One, the cast and crew would gather around him between scenes, watching him drink seas of scotch while reveling them with stories about the good old days. Incidentally, if you ever wondered where the derivative sumbitch came from, it was Gleason. He invented the word to add color to his southern character.

The first crack in Jackie’s aura of invincibility appeared in 1978 when he suffered a heart attack while performing the lead in a revival of the Broadway hit The Sly Fox. A testament to his vitality and will, he finished the play and went out for dinner and drinks afterwards, thinking it was a bad case of heartburn. In the middle of dinner the pain became unbearable and an ambulance was summoned. Jackie underwent triple-bypass heart surgery. When he came to, it was quickly evident that the close brush with death hadn’t changed his mind about anything: “Marilyn (his current wife) gave me holy hell and told me I would never smoke again,” Jackie recounted. “I got out of bed and walked down the hall with all the nurses and doctors chasing me. I got my cigarette and some booze too.”

He made sure his hospital room stayed stocked with liquor and drank his way through his recovery. “An alcoholic doesn’t know why he drinks,” he told a hospital-room interviewer. “I do. I drink to get bagged.”

When Jackie checked himself out, he went back to five packs a day and the usual amount of booze. For lunch he’d have four “whoppers” (double scotches) and a little food to wash them down. The way he figured it, he should have already checked out so from here on out it was all gravy.

Jackie died of cancer at his home on June 24th 1987, at the ripe old age of 71. Ironically enough, he outlived most of those who’d told him to tone it down or else. In accordance with his will, the top step of his tomb was engraved with the phrase: “And away we go!”

It’s hard to fathom how much Jackie Gleason gave to popular culture, and I don’t just mean The Honeymooners, his movies or his music. The Great One also gifted us with the notion that life is to be lived, and to live it fully you have to take risks. A lot of risks. “A safe life isn’t a life at all,” Jackie noted. “Too many people seem to be saving themselves for their wake.”

So if you ever find yourself teetering between taking a chance or playing it safe, ask yourself this: WWJGD?