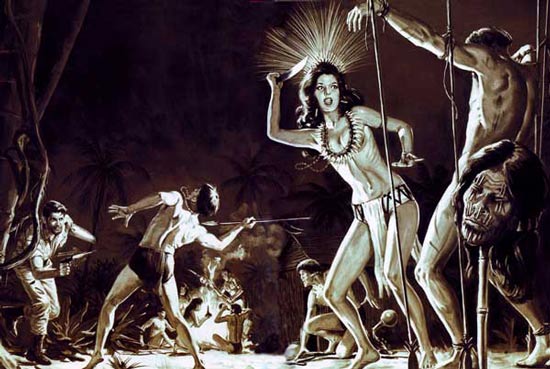

I staggered through the gauntlet of scantily-clad tribeswomen and their brutal staffs rained down like the Devil’s own hailstorm. I gritted my teeth against the agony and clutched the tumbler of whiskey tightly to my chest—because to drop it meant certain death!

My trip to Hell began a week earlier in a filthy bar buried deep in the most depraved slum of Chetumal, Mexico.

I’d been hanging around a dive called the Boca Grande for three months for no goddamn good reason at all. I’d come to Mexico on the G.I. Bill, after I’d served in the Korean War. I studied in Mexico City for six months, then started drinking and drifting. I spiraled steadily downward for three solid years and this was where I ended up—on the bottom, at a filthy little bar in a filthy little town in the middle of a jungle on the Yucatan Peninsula.

Pablo, the Boca’s owner, let me hang around bumming drinks and working grifts because I helped him throw out the occasional rummy. Some nights, if I was still standing, I’d help him clean up the place a little. It hadn’t happened yet, but we both had high hopes.

Boca Grande means Big Mouth in the local lingo and it was the only honest thing about the place. The name was supposed to be in reference to the nearby river, but I never believed it. The joint was a magnet for thieves, con artists and whores who all had one thing in common—big mouths.

The tequila was watered down and the beer, a local native brew, tasted like it had made the trip into town in the bladders of the natives. But if you’re down on your luck, as I was, you take what you get, and if that means chasing watered-down rotgut with swill, then you take it. You don’t like it, but you take it.

I was due for a change of fortune and it came in the form of an Englishman named Trevor Thompson. He walked into the Boca wearing a pith helmet and a pressed khaki uniform with long sleeves and pants. Swear to God. It was fucking ridiculous.

Trevor wasn’t the type you’d expect to walk into a dump like the Boca. In fact, he didn’t look like the sort who’d walk into any kind of bar—he was more of a country club type. Short and ginger haired, he had the look of someone who hadn’t suffered much during his stay on this rock.

He asked Pablo where the “water closet” was and Pablo, as was his way, ignored him.

“He doesn’t speak English,” I told the stranger.

“Oh! But you do! I say, are you a Yank or Canuck?”

“Throat’s dry,” I said, dropping my eyes to my empty beer and tequila glasses. My eyes stayed there until a fresh pair were set in front of me.

“Yank,” I said and knocked back the tequila. You had to knock it down fast, it wasn’t the sort to roll around on your tongue.

“You certainly have a taste for the stuff, haven’t you?” he said.

I downed my beer and Trevor set me up again and ordered a shot of water for himself. I’m not kidding you. Then he made a big deal about drinking it, smacking his lips before and after he shot it with a flourish. Then he looked at me like he’d set an excellent example only a fool could ignore. I somehow managed.

“I’m about to venture forth into the bush,” he went on. That’s how he said it. Like it was the brambles around his Somerset estate. “I’m looking to employ a guide.”

“What’s in the bush?” I asked.

“Something very dear to me,” he said. “Do you know the bush?”

“Yeah, I know it,” I said. Pablo looked up from his newspaper but kept his boca grande shut for once.

Fact is, I didn’t know a damn thing about the local version of “the bush.” Why the hell would I? There aren’t any bars in the bush. But I was working an angle. I’d worked plenty on the occasional tourists who had the rotten luck of walking into the Boca.

I stared at my glasses, freshly empty, and Trevor had them refilled. I sank the tequila and tossed down half the beer. I glanced at Trevor and I could sense my drinking was unsettling him.

“So, what is it, Mayan gold?” I said, feeling I owed him something for the drinks. “Someone sell you a map down at the antiquities market? They’re all fake. It’s the oldest con in the book.”

“It’s my brother,” Trevor said. “His aircraft went down in the bush, near the Mayan ruins at Xpuhil. As you may know, there are no roads to Xpuhil.”

“Bad luck,” I said. I decided to ignore him for awhile, and I was doing a pretty good job until he laid five 100 dollar bills on the bar top. American bills, nice and crisp.

I tried not to stare at them. I hadn’t seen that much dough in a long time. My disposition changed immediately. I knew he was for real now. A real sucker.

“Sorry to have doubted you,” I said, taking on a bit of his brogue. It was an old flim-flam trick. People trust people who talk like them. “So many ill-advised adventurers about. Your brother, you say? He won’t last long in the jungle, that’s for sure. We should get started immediately. We’ll need a native guide and I know the best on the Yucatan.”

Trevor was pleased with my sunny new disposition. I dispatched a boy to rouse my “native guide” out of whatever bordello he was sleeping it off in.

Trevor and I discussed the expedition while waiting for Rico. I brazenly demanded 100 bucks a day, with 50 more for Rico. I expected him to haggle, but Trevor agreed immediately. He ordered up a pair of waters to seal the deal and I went along with it. The man was clearly a lunatic, but his money seemed completely sane.

Then Rico arrived. By his eyes I could see he was deep into a good tequila run, but he was doing his damnedest to play it straight.

I introduced the pair, and for a moment Trevor seemed confused. He probably thought the boy I’d sent out had piled on six woolen coats and came back trying to pass himself off as a jungle guide. Rico is extremely short and extremely wide. Not fat, just built very low to the ground like some of the Maya statues you’ll find sprouting vines in the jungle.

I said, “Rico, this gentleman wants to head into the bush to find his brother. He needs guides. I told him we were the hombres for the job.”

I didn’t wink at Rico or anything, it wasn’t necessary. We’d worked plenty of grifts before. Rico spoke pretty close to perfect English, but he fell right into his role.

“Sí, sí,” he said, his wide Indian head nodding solemnly. “Es posible.”

“He wants to go deep into the jungle,” I said. “To Xpuhil.”

Rico made a face, playing the superstitious Maya to the hilt. “Xpuhil,” he said gravely. “Bad mojo.”

“I know.”

Rico turned away, as if to weigh the worth of his mortal soul against such a powerful spiritual risk. I turned my eyes to Trevor. He was eating it up.

“I will do it,” Rico finally said. “If the dinero es correcto.” I nodded to say that it was.

We all turned to the five bills still laying on the bar top. Trevor reached out and pulled three back into his wallet.

“That should be enough to get us started,” he said, nodding to the remaining pair. “Supplies and the like.”

“When do we get the rest?” I wanted to know.

“As we go,” he said. Which was just what I wanted to hear.

I gave one of the bills to Rico to “buy supplies” and he disappeared out the door. Trevor and I agreed to meet at the Boca first thing in the morning.

We stood there a moment in silence. I was waiting for him to leave so I could have a drink.

“I trust you Mac,” he finally said. “I think you’re a good man.”

I felt sick when he said it. He was a sap, and I couldn’t help that. But it still made me feel sick to my stomach.

Five minutes after Trevor left, Rico slunk back in the door and we laid out our plan over tequilas.

The fact that Trevor was going to pay us as we went meant he would carry the money with him. Rico had told him the trip to Xpuhil and back would take at least ten days, so it would be a bundle.

We would take him out into the jungle, far enough that he would have a hard time finding his way back, then shake him down for his dough. We’d have to take it on the lam for a few weeks, perhaps even leave Chetumal for a while, which was fine by me.

Rico went out to round up enough supplies to fool the Englishman in the morning. I ordered another round, and some of the local Maya came in, fishermen mostly, just like they did every night. They were a loud, jolly bunch, and they liked their drink and they drank it like they earned it. Maybe they did.

They started singing that same damn song, the one they sang every night. An old Spaniard dirge the natives had added a few twists to.

Come on all you bastards

Come on all you losers

Let’s go down to the river

Let’s go drown ourselves

What is life anyway?

Why worry about it?

If the devil doesn’t eat you

The worms surely will.

I finished my beer and went back to my fleabag room at the Balboa Hotel with six bottles of the Boca’s finest rum, which cost me about 20 dollars.

Around midnight I had a decent glow and decided I was going to be anywhere else but the Boca, come morning. The hundred, I figured, was enough. I’d sleep in and Trevor could absorb a relatively cheap lesson.

I’m usually not so sentimental, but I couldn’t stop thinking about what the sap had said, about me being a good man. I tried laughing it off. Maybe I had been a good enough man once. But that was a long time ago, before what happened in Korea.

I woke to a pounding at my door. I knocked an empty bottle out of the way and looked at the clock on the floor next to my cot. Five fucking o’clock in the a.m. I ignored the racket until Rico jimmied my door and stood over my cot.

“Mac!” he shouted, shaking my shoulder. “We must meet the Inglés.”

“Not me,” I said. “I’m going to stay here and drink. We got enough out of that fool.”

“Don’t be estúpido. He has much more to give. He is begging for us to take it.”

“Shove off,” I said and rolled over.

There was silence for a moment, then Rico changed his tone.

“I’ll do it then,” he said darkly. “I’ll tell him you’re sick. I’ll make sure he doesn’t come back to bother us.”

“Go ahead and good luck,” I said, then listened to him retreat out the door.

I tried to go back to sleep, but I couldn’t. I played it all out in my head. I pictured that poor dumb bastard going out in the bush with Rico and probably some other bandit he’d bring on board. They’d march him into the jungle and they’d murder him as soon as they found a quiet spot. They would kill him and bury him in a shallow grave by the river where the ground was soft. I kept picturing him getting his throat slashed by a machete and his fucking pith helmet falling off his head and they would laugh at the poor dumb bastard as they dragged him to his dirty little hole.

After a minute I couldn’t stand it. I got up and was about to yell out the window at Rico when I noticed he was leaning against the door jamb, smiling like a snake.

“I know you, Mac,” he said.

I packed a few things in a rucksack, gathered my hangover and slouched down to the Boca.

If Trevor was surprised to see my smiling face, he didn’t show it. He was wearing a fresh pair of khakis and that goddamn ridiculous pith helmet.

Rico arrived a few minutes later. He’d put together an impressive package, probably all borrowed from his cronies down at the market. Two decrepit donkeys were laden with food, water, sleeping mats, mosquito netting, and machetes—everything three idiots would need to get themselves far enough into the jungle to get themselves killed. After lashing my sack and Trevor’s huge pack to the donkeys, we had a quick drink for good luck—water for Trevor and tequila for the guides—and headed out.

We passed through the open-air market and some of the wise boys I was acquainted with gave me sly winks, congratulating me for reeling in yet another sucker.

It took us just 15 minutes to reach the edge of the jungle. The town is surrounded by it. Rico led us off the main road almost immediately, explaining there were only foot and donkey paths leading to where we wanted to go.

To be honest, Rico wasn’t just another rum-dumb Indian who made a living by lying to everyone he could point his mouth at. He’d been a real guide once, before he realized there were easier ways to make a buck.

We hadn’t marched a mile when I started cursing myself for getting off my cot. By midday it started to rain and the jungle turned into a steaming, humid hell. We stopped by a stream to rest and I pulled a quart of warm beer out of my sack. I’d sweated out every ounce of alcohol in my system and my head was starting to ache.

Trevor didn’t say anything. He just stood there looking at me, acting disappointed, just like my brother Mike used to.

“You want some?” I asked after tipping half the bottle down my throat.

He shook his head no.

I drained the rest of the quart and threw it in the stream, thinking, if you’re disappointed in me now, just wait a while.

A couple hours later we topped a small rise and came into a small clearing. Rico stopped and took a careful look around. It was time.

I admit I’d been dreading it. Dreading that look on Trevor’s face when he realized how good a man I really was. I’d tried rationalizing it. He obviously had plenty of dough, and all he’d get for his trouble was a knot on his head and a long walk back to town. I’d probably save him the hassle of getting skinned alive by the natives.

But when Rico gave me the look, the look that said I was supposed to let our sucker know the score, I couldn’t do it. Instead I pulled a bottle of rum and my Colt .45 service automatic out of my sack, walked over to a fallen tree and sat down for a drink.

“What’s wrong?” Trevor asked. He didn’t sound suspicious or anything, just a little curious. “Are we making camp already? Plenty of daylight left.”

Rico stared at me and I looked away. His wide, dark face creased with disappointment. Everyone was disappointed in me.

Rico sighed and said, “We have a problem, señor.”

“Problem?” Trevor asked.

“Sí. We need your money.”

Trevor frowned and I wanted to laugh. He still hadn’t caught on. “My money?” he asked.

“You heard him,” I said angrily, taking a good belt. “We want today’s wages.”

Rico gave me a funny look, then smiled. We would watch where the money came from and save us the trouble of searching him.

“That seems fair,” Trevor said, eyeing the .45 hanging from my left hand. He reached under his shirt, unzipped a money belt and pulled out a hundred and a fifty dollars.

What happened—or didn’t happen—next I would come to regret for the rest of my life.

What I didn’t do was konk Trevor on the head with the .45 and take his money. What I did do was shove my .45 into my belt, take my hundred, hand Rico his fifty, take one more jolt of rum, and put the bottle back in the sack. Then I told Rico to get moving.

If you could have seen the look on Rico’s face, you would have laughed your head off. It was confusion and hate and every ugly emotion in between. He tried to speak to me in Spanish and I touched the butt of my .45. Cursing colorfully, he headed off into the bush.

He cursed every step of the way until we made camp at dusk. When Trevor went  into the jungle to relieve himself, Rico crept up to me like a jaguar sniffing around a cow that might be a bull.

into the jungle to relieve himself, Rico crept up to me like a jaguar sniffing around a cow that might be a bull.

I told him we were going to find Trevor’s brother. When he asked why, I told him I’d found out that the plane he’d went down with was loaded with gold and jewels looted from a Mayan dig. Tens of thousands of dollars worth.

At first he didn’t believe it. He seemed mostly to believe I was working a side scam, that I was going to bump them both off so I wouldn’t have to split the dough. But eventually greed overcame suspicion. In his mind it was the only angle that worked. If I had wanted to bump them both off, I would have done it back at the clearing.

It took me a while to figure out my own angle, but I finally did. See, if you don’t like yourself, you’ll go far out of your way to screw up your life, to punish yourself. And I hadn’t liked myself since I got my brother killed in Korea.

The thing about the jungle is, you can’t get away from it. You could run screaming like a lunatic for 50 miles in any direction and you’d still be right in the middle of its green, humid, chattering hell. And you’d probably find yourself waist deep in quicksand with a friendly jaguar trying to rescue you with its claws.

The first three nights we didn’t bother to build a cook fire. We were too tired and dispirited. By the fourth night we had to build one because we ran out of canned food. So we sat around the fire breathing smoke, waiting for hard black beans to soften into something semi-edible.

I got into my rum and Rico laid into his private supply of tequila. To my surprise, Trevor took out a silver flask and tossed it to me. After I had a taste I wasn’t so surprised. It was sugar water.

“It’s my brother’s,” he said. I examined the flask by the firelight. To Howard, the inscription read. Good luck in the bush. Your loving brother, Trevor.

“Why didn’t he take it with him?” I asked.

Trevor shrugged and I passed the flask to Rico.

“Do you have any siblings?” Trevor asked.

“A sister in Topeka,” I said. “A brother.”

“Where’s he?”

“Korea.”

“Oh? Did he fall for a local girl?”

I looked into the fire, now burning down to orange and black ember. Mike fell, all right.

Rico choked and spit a stream of sugar water into the embers. “Mierda,” he hissed, wiping his lips. He passed the flask back to Trevor and said, “Your brother, he digs for things?”

“That’s right,” Trevor said, then looked directly at me. “We all dig for things, don’t we?”

“Not me,” I said, taking a good pull. “I’m more about filling up holes.” I thought that was funny and laughed, because it was true. I preferred things to stay in the ground, where they belonged.

Trevor got up and excused himself. He went out into the darkness and Rico whispered, “Disentería.”

I nodded. A case of dysentery might explain his frequent trips into the jungle, and his wan complexion which seemed to get worse by the day.

Trevor came back and immediately went to sleep under his netting. It wasn’t long before Rico was snoring right along with him.

I sat alone in the middle of the jungle night and thought, We’re all going to die out here. And you know what? I don’t give half a damn.

When we woke on the fifth day our donkeys were gone. Stolen by natives, Rico guessed. Not that we needed them. We didn’t have much to carry. We were down to a few sacks of beans and flour and half a bottle of rum.

On the sixth day Rico said we were close. We spent half the afternoon climbing a hill then took a look down at the sea of jungle.

“Xpuhil is there,” Rico said, pointing at a patch of green. “Where the water meets.”

I squinted my eyes against the descending sun and was able to make out three stone towers rising out of the canopy like a trio of gray ghosts. Trevor and I exchanged uneasy looks. We started down the ridge.

The towers stretched like long fingers from a two-story stone temple strangled with vines. We climbed the wide set of steps to the first level to face strange gods staring blindly from columns of weathered stone. Rico acted spooked and ready to bolt, and I was pretty sure he wasn’t putting on a show for Trevor’s benefit.

We climbed to the second level, walked around to the back and spotted the plane.

It was a Grumman Albatross, a twin-prop amphibious cargo runner. The Navy boys used them in Korea. From a quarter mile away it didn’t appear in too bad of shape, if you overlooked the fact that both wings were sheared off.

“He was probably trying to put down in the water,” I said, “and overshot the bend in the river.”

“I would say you are exactly right,” Trevor said.

The sun was beginning to set, but it was a cinch to follow the debris path to the Grumman. When we got close it was my turn to get spooked. The battered metal hulk looked more haunted than any 2000-year-old temple. And this one had a much better chance of containing at least one ghost.

The cargo door hung open like a gaping mouth. Too my surprise, Trevor immediately leapt into the dark interior and shined his flashlight around furiously.

“Those bastards!” he said.

“What is it?” I said, following him inside, ready for a grisly scene.

Except there wasn’t one. The cargo compartment was bare except for a pair of battered wooden crates the size of steamer trunks.

“Better check the cockpit,” I said. Trevor blinked at me, then moved forward.

I pointed my flashlight at the crates. Both were stamped with black ink, bearing the name of an old friend I hadn’t run across in a long time: Johnnie Walker Blended Scotch Whisky.

“Nothing,” Trevor whispered with despair, creeping back into the cargo hold. “Nothing at all.”

I lifted the askew tops of both crates, hoping against hope. The bottom of each sparkled with broken glass.

“Not a damn thing,” I said, more than a little despairing myself.

An hour later we sat watching the light of our campfire dance on the face of the temple 50 feet distant. If you watched it out of the corner of your eye the old gods seemed to be shifting, moving. A real spook-house effect, but I figured it was better than camping near the plane, as Trevor had wanted.

“Where’s the nearest village?” Trevor asked Rico. “Perhaps they can tell us what happened to Howard.”

Rico shrugged as he stirred our last pot of beans. “Tomorrow I will scout around and see if I can find a trail.”

“That won’t be necessary,” I said. “If we build this fire high enough, they’ll come around. And we’ll be ready for them.”

We lay atop the second level of the temple, watching the camp below. Rico squatted next to the towering flames, a lonely castaway surrounded by a sea of darkness.

“How did you know your brother crashed the plane?” I asked.

“Radio transmission,” Trevor said, his voice trailing off.

“Was he running booze to the natives?”

Trevor laughed. “Not bloody likely. Could you imagine wasting Johnnie on these fucking savages?”

The bitterness in his voice caused me to glance at him. In the moonlight his face shone alabaster white. He seemed agitated, sweating more than usual.

“It was for his own use,” he said. “My brother had his own holes to fill.” A cruel smile curled his lips. “And what about your brother, Mac? Did he drink himself to death like you intend to?”

“Mike never had a drink in his life,” I snarled.

“Then what’s the mystery, Mac? Why do you cloud up like Cain when you mention his name?”

I suddenly resented not letting Rico smash his head a week ago. I wanted to take the .45 in my hand and smash his face right then.

“Sorry,” he said, his voice softening to a whisper. “I’m in a bad place. What was he doing in Korea? Was he drafted?”

“I talked him into going into the Army with me,” I said, wishing like hell I had a drink. “He wasn’t cut out for it. He was too soft for the Army and he was way too soft for Korea.”

“Did he—”

“I killed him just like Cain,” I said, watching a line of torches emerge from the jungle from the direction of the river.

THE torch bearers, two dozen of them, walked into the light of the campfire. Rico rose slowly and appeared to talk to them. After a moment he joined the procession and they headed back the way they came.

I heard Trevor shift and turned to watch him reach into his bag and take out what looked like a car jack. What the hell? I thought, then recognized the ugly shape of an M3 .45 caliber submachine gun. What we called a “grease gun” in the Army.

“You know how to work that thing?” I asked.

“Just watch me,” he said, moving quickly down the temple steps.

We stayed 50 feet behind, and after half an hour of stumbling blindly through the darkness, we reached the edge of a village lit by a large communal fire pit. About 50 natives—men, women and children—were gathered around Rico. Rico spoke quickly in a Mayan dialect, repeatedly pointing back to our camp.

I reached for Trevor’s shoulder, to signal that we should reconnoiter a bit, but he was already stepping into the light.

“Don’t move!” he yelled, pointing the grease gun at the center of the group.

As one, the crowd turned to face him.

“El diablo rojo!” an unusually tall woman brandishing a long spear said, then spat at the ground.

“Where is it?” Trevor demanded in perfect Spanish.

“It?” I said, taking his flank.

“They know what I’m talking about,” he said, and to make sure, he squeezed off four rounds into the nearest native, a teenaged boy.

The slow-moving .45 slugs lifted the boy off the ground and threw him into the fire, where he immediately began to sizzle. About half of the natives took off screaming into the forest and Trevor let them go.

Of the remaining 30 or so natives, almost all were female. Rico hesitantly detached himself from the group and crept back to where I stood, giving Trevor a wide berth.

The tall woman with the spear moved slowly forward until she stood no more than ten feet away from us. She seemed to be in charge and furthermore, she seemed to have met Trevor before.

“We drank it,” she said in pidgin Spanish, shrugging her broad shoulders.

“Not that, you dumb whore,” Trevor said. His tone no longer suited a country club. It seemed more at home in a Cockney pub.

She frowned, then smiled broadly, wrinkling the long scar down the side of her jaw. She took three more steps forward, laughing wickedly.

She frowned, then smiled broadly, wrinkling the long scar down the side of her jaw. She took three more steps forward, laughing wickedly.

Trevor took a step back, the submachine gun trembling in his hands.

“Don’t shoot!” Rico shouted. “This is Marta. She is the leader of the tribe. She—”

Marta turned, as if she were going to walk away, then suddenly spun back around and slashed her spear downward in a long arc. Trevor tried to jump backward, but the head of the spear struck the barrel of the M3, knocking it to the ground.

Without thinking, I pointed the .45 at her head and pulled the trigger.

But nothing happened. I tried again, then looked down at my hand. It was lying in the dirt, still gripping the pistol.

I numbly watched the blood spurt from the stump where my hand used to be, then looked at the bloody machete in Rico’s hand. I was about to tell him how I felt about the whole thing when a freight train collided with my head and the world went black.

You wake up and you think it had to have been an evil dream; nothing that horrible could be real. Then you open your eyes and the sun is up, your hand is gone and you realize the nightmare is real. The nightmare is real and it’s just beginning.

I sagged between two stout poles driven deep into the ground, my right wrist bound to one, my left forearm to the other.

The only good news, if you can call it that, was the ropes were so tight it had stopped the bleeding from my stump.

My stump. That was going to take some getting used to. Trevor slumped next to me in a similar configuration, except he still had both his hands. What he didn’t have was some of his teeth. Burns and torture wounds crisscrossed his naked torso and I was fairly sure he was dead.

I turned my head toward the fire pit. A handful of natives squatted around it, preparing a meal.

“Mac,” I heard. I turned to Trevor. As far as I could see, he was still dead. I turned to my left and there stood Rico. My .45 was stuck in his belt. He shook his head sadly. I turned away. I couldn’t stand to look at him.

“Sooooorry, Mac,” he said. “I had no choice.”

Rico told me a story. He told me there was no gold. There was no brother. He said it was Trevor who had crashed the plane. It was Trevor who had killed three of the tribe before escaping down the river in one of their boats. He had lied about everything. Even his name. His name was Howard.

“Why did he bring us here?” I croaked, my throat dry as gunpowder.

“He came back for his heroin,” Rico said. “He was smuggling it from Brazil to Mexico City. He hid it in crates, under bottles of whiskey. Look at his arm! He’s a junky himself.”

I didn’t bother to look. I knew it was true. It explained everything.

“Do you think he would let us live after we helped him take his drugs down the river?” Rico asked, then shrugged. “The natives don’t know heroin from banana leaves. There is at least $100,000 worth. There is a mining town a couple days down the river.” He shrugged again, as if to say it was business, nothing personal, then walked away.

So there it was. Everyone had worked an angle except for me, the bright boy. The biggest sap in Mexico.

I woke up to a pair of hard slaps to my face. I opened my eyes and looked at the hand doing the slapping. It was mine. It was starting to shrivel a little but otherwise looked pretty fair. It dangled from the shaft of Marta’s spear like a trophy. Behind her stood the entire village.

“Why do you slap yourself so?” she asked in crude Spanish.

“Because I hate myself,” I said, getting a pretty good laugh from the crowd. Marta shouted an order and a group of women untied my ropes. They dragged me to an outcropping overlooking the river, then held me over the edge so I could catch the view. And what a view. A hundred feet below, jagged black rocks lined the shore. Among the rocks were broken bones and smashed bodies in various degrees of decomposition.

They threw me to the ground, and Howard (Trevor to his friends) dropped like a sack of gravel next to me. The eye that wasn’t swollen shut blinked at me. He seemed more surprised that he was alive than I was.

They threw me to the ground, and Howard (Trevor to his friends) dropped like a sack of gravel next to me. The eye that wasn’t swollen shut blinked at me. He seemed more surprised that he was alive than I was.

Together we watched two dozen tribeswomen line up in two opposing rows, forming a long gauntlet. They all held six-foot-long switches.

Marta grabbed me by the hair then handed me a half-full commemorative Johnnie Walker Black glass tumbler.

Well, I thought, instinctively downing the scotch, she isn’t entirely lacking in social graces.

Strong liquor isn’t the best thing for a parched throat, but to me it tasted like mother’s milk.

Marta screamed something at me, then barked at Rico. He dutifully refilled my glass from a full bottle of Johnnie.

I downed it immediately, earning myself a kick in the back, courtesy of Marta’s size 11 foot.

She screamed gibberish at Rico and he said, “You can’t drink it until you do it.”

“Do it? Listen, if she’s thinking about getting sexy with me, I’m going to need more than that bottle.”

Rico smiled politely. “They want you to run the gauntlet,” he said. “It’s an old Maya game, except they used to use human skulls filled with blood. If you spill, they . . .”— his eyes flickered toward the cliff — “. . . they spill you.”

“And if I don’t spill . . .”

“You go free.”

He managed to keep a straight face for about two seconds, then laughed uproariously. “I kid you, patron. If you make it, you have to drink the whiskey. And try again. Until the bottle is empty.”

I looked down the rows of women. Their heavy breasts swayed and their switches trembled in their eagerness to get the game started. Rico refilled my glass.

“Thanks,” I said, then sank it like a cardboard battleship.

Marta drove the non-lethal end of her spear into the middle of my back and I collapsed in agony. She turned the spear around and tickled my throat with its point.

“Fine,” I said. “I’ll play.”

Rico filled the glass to the 3/4 mark. I stood up and faced the gauntlet.

I moved slowly at first, as if in a stupor, then lunged into a sprint, gripping my tumbler like a fullback protecting the ball as he crashed through the secondary. I caught the first half dozen on each side completely by surprise, their sticks cut the air behind me like angry insects. The remainder got in their licks, but they were rushed and their blows glanced off my shoulders and back with hardly any force at all.

Two men pointing spears halted me a the end of the gauntlet. The ladies roundly cursed me as a cheater while I caught my breath, then downed the scotch.

Things could be worse, I thought, imagining how it must have been in the old days, when you got a skullcap full of blood to reward your run. I could already feel Johnnie creeping into my bloodstream, and a little hope sparked in my heart. Where there’s hooch, there’s hope.

It was Trevor’s turn. After watching my successful run, he seemed to have roused himself a little.

“Any advice?” he asked through the tunnel of women.

“Pretend you’re parading down Piccadilly,” I said, “and it’s just confetti coming down.”

He smiled faintly, put one hand over the top of his glass, and lumbered forward.

There was no artifice or surprise in his run and he paid dearly for it. They shrieked with bloodlust and laid into him mercilessly, some of them even managed to strike him twice. He tripped a couple times but stayed on his feet until he collapsed beside me, quivering with pain. He raised his glass. He didn’t spill a drop.

“This is the part I really hate,” he said, then tipped the glass to his lips. He made a face but kept it down.

The hue and cry went up and the bottle was passed down the line. One of the spearmen filled my glass until the Scotch spilled down the sides. He smiled cruelly, thinking himself clever.

I got to my feet and took a deep breath. They would not be surprised this time; they held their switches high, tensed to strike, their breasts heaving with anticipation.

It’s all screwy, I thought. Here I am chugging good Scotch, surrounded by excited, half-naked women, and you know what? I’m not having that great of a time.

I hunched over, pressed the glass’s mouth against my solar plexus, forming a tight seal, and started forward.

The blows began immediately, and with gusto. The girls were really putting their backs into it this time. I bent lower over the glass, tucking my elbows in tight, and focused on each step. Twice the pain became so intense I thought I’d drop the glass, but I held on. I’m a bonafide expert when it comes to not spilling booze. I practically built a lifestyle around it.

I found myself yelling, “Knock it off!” over and over again, and when I reached Marta she must have thought I was talking about my head because she swung her spear like a Louisville Slugger and tried to knock my skull into the treeline.

I blacked out for an ugly second, then made a final lunge, landing at Rico’s feet. I felt a sharp pain in my stomach and I looked beneath me to see I was lying on my glass. My full glass.

I drank it slower this time, noting mellow, woodsy undertones that would have danced on my palette were it not mixing badly with the blood running down my face.

I heard a roar and turned to see Trevor making his run. He had a new tactic. He bounced down the rows like a pinball, crashing into one side then the other, causing the girls to miss and strike one another. By the time he reached the end and downed his Scotch, a pair of eye-scratching, hair-pulling cat fights had broken out. Marta rushed toward them, howling like a banshee.

“That’s it,” Trevor said, sitting down hard beside me. Blood was running into his good eye from a large jagged wound across his forehead and he spoke hoarsely around broken teeth and mashed lips. “That’s all I can do.”

“Look at the bottle,” I said. Three or four more runs and it’ll be empty.”

“So what? Do you really think they’ll let us go?”

I didn’t reply because I knew the answer.

“You told your brother it would be a big adventure, didn’t you, Mac?” Trevor said. “And he got killed.”

I watched Marta try to break up the fights by savagely beating the combatants with her spear. When that didn’t work, she started stabbing them in the ass with the point.

“Well,” he continued. “I did the same to you. So it’s all square. The hole is filled. If you can survive this, you’re free of any blame. You can start over again.”

The laughter started low and quiet, then climbed the scales as it got louder. I looked up. It was Rico.

“The hole is a little deeper than that,” Rico said. “Mac killed his brother over a whore in Seoul.”

I was almost relieved when Marta stormed back after squaring away her little sorority. I held up my glass, eager to get on with it because I could feel Trevor’s eyes upon me, judging me. He’d put us in this hell, and there he was, judging me.

When my glass was full, I put my forearm over the top and walked into the gauntlet.

The switches came down. Each of them got at least three swings at me. I don’t know if it was the booze or what, but I didn’t feel anything. It was like it was happening to someone else, and I was just watching and not terribly interested in how it turned out.

When I reached the end, I lifted my glass and poured it straight down. It was the best drink I ever had.

I heard the switches rending air behind me, beating Trevor like a cheap drum, and I didn’t turn around. I waited for him to fall down beside me but he didn’t. The thwacking just went on and on.

When it finally stopped I turned around. Trevor lay face down on the ground. He’d made it about halfway. There wasn’t an inch of his body that wasn’t leaking blood. His spilled drink lay beside him.

“I never killed my brother,” I yelled.

Trevor raised his head very slowly. His face was a mask of blood.

“He fell on that knife,” I said. “The whore pushed him.”

He lowered his head and that was it. He was gone.

They rolled him to the side, clearing my path.

With a satisfied expression, Marta sent the whisky down the line.

If you can’t come up with a good speech when you’re standing on the gallows, Voltaire once said, then you’ve lived a lousy life. Something like that. So when the bottle got close, I grabbed it by the neck and held it high.

“Attention, harlots!” I shouted at the top of my lungs. “This is Johnnie fucking Walker! This is good Scotch. A lot of men, a lot of good men, worked hard to make this booze. It was not made for a bunch of whores to play silly fucking games with!”

Marta howled with fury. She couldn’t understand much English, but she sure as hell knew when she was being insulted.

“It was made to drink,” I said, then leveled the bottle into my mouth. I let it roll down, and with each swallow I felt myself get stronger, angrier, meaner.

Rico was right. The hole wasn’t full. Not by a long shot.

By the time the last drop rolled down my throat, Marta was barreling down the gauntlet with her spear held high, just as I had hoped.

I threw the bottle in the air and she instinctively tried to stab it with her spear, allowing me to step under its point and hit her flush on the jaw, knocking her out cold.

I stepped on her head as I ran down the rows. Not a single switch came down, and by the time I reached Rico I was moving at full speed. I hit him like a freight train and over the cliff we went.

My brother taught me how to dive. The secret, he told me, was to imagine your body was a knife and the water was the heart of someone you wanted to kill.

Sometimes the knife will glance off a rib bone, and I glanced off Rico after he got hung up on a jagged rock. My shoulder hit submerged gravel and I executed a spectacular somersault into the river. I was stunned but sensible enough to struggle my way to the muddy bottom. I looked up to watch the current tug Rico off his rock and carry his corpse downstream. More importantly, I watched my pistol slip from his belt and tumble in slow motion toward my waiting hand.

I waited until nightfall, then crept out of the shallows and into the jungle. I paused outside the village to listen to them hollering and carrying on around the fire. It sounded as if my heartfelt Johnnie Walker sales pitch had sold them on the product.

Killing them was easy. Let’s say we had a history.

The first one I met was stumbling toward the treeline to relieve himself as I was walking out of it. With a little grin, I recognized him as the one who’d overfilled my glass. Never thought I’d kill a man for that, I thought, shooting him once in the head.

I continued forward. There was only a half-assed rousing to the bark of the .45, that’s how far they had walked with Johnnie. It wasn’t until I shot two more, a man and a woman fooling around next to a hut, that the party started grinding to a halt.

Trevor was back on his poles. Just hanging around. I stopped beside him, then heard a shriek and turned to see my old drinking buddy Marta rushing at me with her spear, not unfamiliarly. From a scant 20 feet away, she reared back and let it fly.

>

My hand knocked it off course. Not my right hand. My left hand, the one tied to her spear. It totally screwed up the spear’s aerodynamics.

It made a wet thunk as it went through Trevor’s chest and came out halfway on the other side. That’s not my fault, either, I thought, then shot Marta in the back as she tried to run away.

She fell into the fire, just like the boy Trevor had shot. It was priceless. I parked the pistol under my left armpit and lifted Trevor’s face by his hair. I looked into his one good eye. It was dead, just like him.

By this time the locals were starting to get the idea they should clear out. I wanted to run after them. I wanted to kill them all, every last one.

Instead, I managed to kill only two, maybe three more before they’d all made it into the bush. The bush, I thought. That silly sonuvabitch. He knew it was a jungle all along.

I was halfway to the river when I remembered the cargo. The stuff that everyone was dying over. I knew there were plenty of people in the nearest town that would be more than happy to take it off my hands. There was never enough to go around with those types.

It took me half an hour to load a medium-sized outrigger canoe with as much as it would carry. I found out I wasn’t much of a paddler anymore, so I let the current carry me.

It took me three miserable days to reach the mining town of Manao, but only half an hour to find someone willing to buy. I sold it at a bargain basement rate, making just enough money for a meal, a visit to a doctor, and a bus ticket to El Paso. I sold it all but three bottles, enough to keep me company on the long ride home.

by Charlie “Chisel” MCMahon, as told to Frank Kelly Rich